Your annual Like a Dragon correspondent is reporting nine months after completing the longest, most sprawling game in the franchise yet. A direct sequel to 2020’s Yakuza: Like a Dragon, Like A Dragon: Infinite Wealth continues the story of Ichiban Kasuga and maintains that game’s turn-based combat with new character classes, character synergies, and a whole new setting in a version of Honolulu City.

I will start here by saying that unlike many other games in the franchise, this is firmly not a convenient place to jump in. Infinite Wealth starts with a two hour prologue that almost exclusively references the events of the previous game, and discussing the very premise of Infinite Wealth basically requires spoiling the 2020 title, as well as Yakuza 3-6 in varying degrees of detail. Many of the game’s narrative payoffs and rewards also involve easter eggs, recurring cast members, and an entire sidequest system required to make longtime franchise protagonist Kazuma Kiryu stronger, the Life Links system, involves reuniting with characters from previous games who may have been left on the sideline.

This is, essentially, your final warning, because in order to discuss what makes this game worthy, I have to dig into some of those Yakuza series spoilers. Suffice it to say this game has rewarding JRPG combat, enough minigames and side quests to rival Super Mario Party Jamboree, and a story more focused on character work and fan pleasure than on the social commentary and broader political intrigue of the previous title. I also will end this with a spoiler section about Infinite Wealth itself, because I want to expand a bit on why it isn’t higher for me.

Ichiban Kasuga continues to reside in Yokohama’s Isezaki Ijincho precinct, where he helps ex-yakuza “orphaned” by the mutual dissolution of the Omi Alliance and Tojo Clan go straight in a society that looks down on them. He’s treated as a town hero for his role in exposing conservative politician Ryo Aoki and his Bleach Japan reactionary movement as corrupt and fascistic, but even with his newfound popularity, he’s still emotionally stunted by his eighteen years in prison. Unfortunately, someone’s decided to turn their sights back on him for his role in the end of the yakuza, and a V-Tuber uses misrepresentative footage to get him and his friends out of their jobs and back to investigating the underworld of Yokohama.

This investigation leads him to an opportunity – lay low for a while, go to Honolulu, and meet his long lost mother Akane. Things quickly go awry upon arrival – the game’s previews showed Kasuga nude on the beach, not remembering how he got there, and at the mercy of Honolulu’s police force. He’s rescued by Kiryu, who reveals that in his sad late-in-life exile, he’s been diagnosed with late stage cancer. Most of the people who love him are already under the impression that he’s dead, part of an exchange he’s made with the black ops Daidoji political faction – but the question remains whether or not he will die quietly or fight to get his life back.

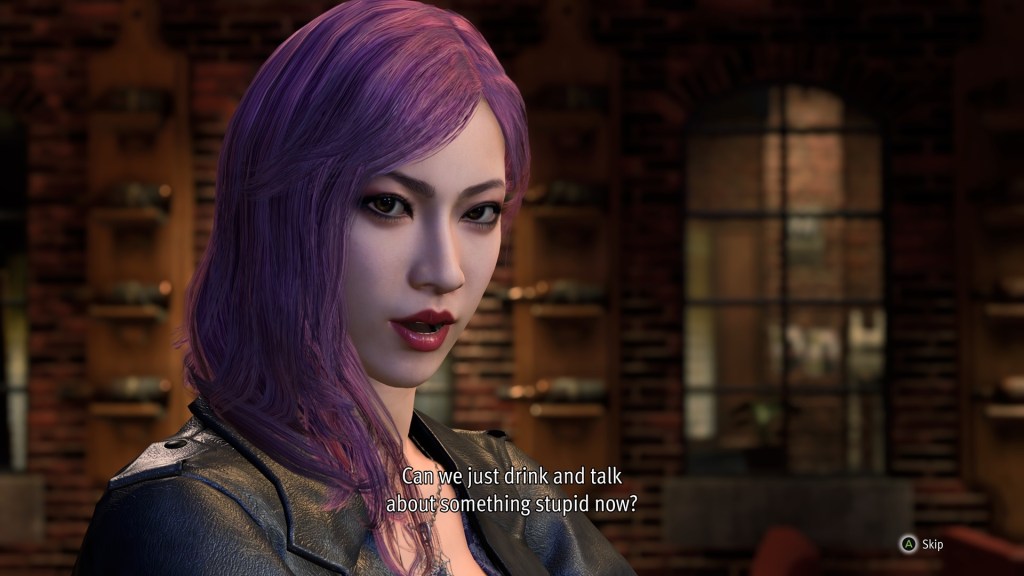

The two men begin investigating the sudden series of events that have brought them both to Honolulu, the culmination of several criminal factions all seemingly looking for Ichiban’s mother. I’ll be honest – outside of what this maneuvering offers our characters in terms of character development, cool setpieces, and comedy, don’t worry about it too much. This isn’t the franchise’s most successful conspiracy. It does introduce some new party members, whose stories offer memorable twists and charming personalities, and have room for a lot of old friends. Two highlights are Chitose Fujinomiya, stylish scammer and bright new party member, and Yutaka Yamai, terrifying enemy heavy who finds himself chilled to the bone in the middle of blazing fire.

Where Infinite Wealth finds its narrative strength is in offering Ichiban and Kiryu personal challenges to overcome with those who want to help them. Ichiban’s emotional immaturity and naïveté are preventing him from developing romantic relationships in appropriate ways or from allowing him to appropriately grieve the life he missed out on, and the game’s emphasis on healthy relationships makes his emotional growth a real focus. Meanwhile, Kiryu, the unflappable, indefatigable man who can punch his way through any hardship, must finally learn to accept help, deny fate, and be vulnerable. The game builds systems around opening opportunities for that growth, and it really is a nice story when you get over the letdown of its loose plot.

The game also pummels you with miniature campaigns of side content to pursue. Pocket Circuit, games like mahjong and shogi, karaoke, and arenas all return, sure. But now this game adds a crazy taxi based delivery campaign. Sujimon, the gag for the previous game’s bestiary, has been expanded into a full blown gacha collection battler with four gyms and a Sujimon League championship. An island tourism management game named Dondoko Island pokes fun at Animal Crossing while offering an eight hour campaign of fulfilling guest requests. There’s a Pokemon Snap equivalent where you shoot pictures in on-rails tourism rides. That’s all before you get to the franchise’s signature side quests, which are as plentiful and quality as ever, or the two megadungeons designed to promote level progression throughout the game rather than saving it for one rude difficulty spike right at the game’s conclusion.

The RPG combat of Infinite Wealth is far better balanced and offers much more variety than the previous title as well. It is much easier to combine movesets of different classes to make each character more unique, and the level progression is a lot smoother over the course of the game. The flow of fights is snappier, and character geography is much more rewarding to manage with more follow-up hits and combo attacks. The ability to rush down opponents lower enough leveled than yourself for a moderate XP hit (something like .7x XP for an auto-win?) makes traversing town a lot easier, too.

Like A Dragon: Infinite Wealth makes several much-needed corrections from the previous RPG, taking the gameplay where it needed to go in order to stand alongside a renaissance of turn based RPGs. I cannot personally argue that Infinite Wealth is the best game in the franchise’s recent run. I prefer the story of Yakuza: Like a Dragon and Like a Dragon Gaiden: The Man Who Escaped His Name a little too much to put it forward as champ. But given the strength of its polish, it might be yours.

With that, I’d like to say a little bit more about why – this is your last warning for Like A Dragon: Infinite Wealth spoilers!!!

I maintain my feeling from the 2020 Game of the Year write-up I did that the first Ichiban Kasuga RPG really achieved something profound in telling a story that commented meaningfully on rising puritanical fascism and social inequality. The start of this game, focused on the fact that these ex-yakuza now are so ostracized that they can’t find work, really felt like a continuation on that attention to detail. The way the game ultimately builds toward a plotline where these ex-yakuza are being exploited by a supposedly goodwill rehabilitation company is, itself, following the storyline goals that I’d enjoyed the series setting forward. While there is a sense of “okay, I kind of hoped dissolving the formal Yakuza in the last game meant we needed to seek new stories,” I enjoyed the way this game handled the feeling that you’re never quite out in a society that stigmatizes redemption.

Tying that to YouTube cancel culture would be messy, but interesting! As a leftie, it’s compelling to examine the way the popular left masses (read: not people who actually, seriously, craft ideas for prison abolition, but People On Twitter or whatever) discuss prison abolition and then offer so little reparation or redemption to those who had a problematic post eleven years ago. The game also engages with YouTube bullying, though in a less adept way than previous RGG Studios title Lost Judgment did a couple years ago. Unfortunately, the game never actually ties these themes together – the YouTube cancellation ends up being part of a specific revenge conspiracy by the game’s ultimate villain, having nothing to do with societal opinion or ideological hurdles beyond “it’s easy to sway the masses.” This whole thread ends up making a pretty satisfying individual character arc for our V-Tuber (surprise: it’s Chitose!,) but it lets down any attempt to engage with the ideas beyond “yeah, they’re in the game!”

But really, if I had to say my biggest issue, it’s just that the villains are lame and have nothing valuable to add to the story. The guy who’s kidnapping Ichi’s mom and the little girl heiress to the Palekana organization is the flattest “I am corrupt and want power” villain the franchise has ever seen. Dwight sucks, and the Danny Trejo stuntcasting feels like it’s purely a diversion to keep you off the trail of the main storyline. The ultimate villain, Ebina, basically feels like a watered-down retread of jealousy and resentment ideas explored better in the previous game with the young master Masato Arakawa, and his desire to poison/take revenge on the yakuza feels too supervillainous and melodramatic to really feel like it’s saying much of anything.

While I admire a lot of the character work for Ichi and Kiryu, I also feel like they both stop just short of really perfecting their arcs, too. Kiryu is a little easier to discuss. 2023’s Like a Dragon Gaiden: The Man Who Erased His Name explores what Kiryu’s been doing since he faked his death in Yakuza 6: The Song of Life, and it’s become infamous to franchise fans for its tearjerker ending. I’d heard that Kiryu is diagnosed with terminal cancer in Infinite Wealth before playing Gaiden, so I assumed that diagnosis is what would hit people in the gut. But instead, it’s a devastating act of kindness – Kiryu’s Daidoji handler, Hanawa, sets up a spycam so he can see the kids from the orphanage tell his staged grave how life has been going. Voice actor Takaya Kuroda gives an astonishing performance of grief during this sequence as Kiryu watching his loved ones grow and succeed and knowing he’ll never see them again.

It’s an emotionally deft ending, one that is unfortunately wholly unreferenced and is in fact almost undone by Infinite Wealth. Even from the game’s start, it’s immediately apparent that Gaiden was written after Infinite Wealth was completed, so the relationship between Hanawa and Kiryu is immediately less intimate and specific than we’d seen in Gaiden. Kiryu’s cancer diagnosis puts things on a running clock, but he’s seemingly more eager for adventure than he was in the previous game.

Then, during the course of the game, the Daidoji Faction effectively gets wiped out, Kiryu being alive is all but unveiled to the public, and he’s reunited with basically every single character he’s ever encountered, either face to face or as an eavesdropper. Some of these sequences are excellent – others, like the boss fight against three previous franchise icons, are melodramatic and not totally satisfying, though that one is at least mechanically pretty cool. It all culminates in feeling like this is a walking funeral, Kiryu minutes from the grave. I think ending on his death probably would have been too much, but it kind of just ends on a shrug, almost setting up that he’ll still be around for yet another death next game. It almost makes me wish Gaiden had been the goodbye, as much pleasure as it was to have him around in Infinite Wealth.

Ichi’s arc is actually pretty great, but it has almost nothing to do with the game’s story. I haven’t mentioned this at all yet, but during the game’s early hours, Ichi asks the previous game’s primary female party member Saeko Mukoda on a date after a couple years of friendship, and she agrees. However, he basically missed his entire young adulthood to being in prison when he took the fall for Masato, and he’s never actually been on a date before. It turns out to be a pretty decent date! But at the end, he gets so caught up in his immature fantasy that he proposes to her before even telling her that he actually likes her romantically – she, furious, politely ends the date and then refuses to speak to him until well into this game’s storyline.

This arc, ultimately, is about Ichi realizing that even though he’s “the hero of Yokohama,” working hard to improve the world and save his friends, he’s still completely ignorant about money, love, and all the basics of adulthood. His incarceration, combined with his already quirky personality, have left him a child in a grown man’s body. There’s a little bit of this tied into the main plot, with Ichi wondering what he’ll actually have to say to his long-lost birth mother, and their climactic conversation is sweet, understated, and helps show the growth Ichi’s been on during the game. But it has absolutely nothing to do with the conspiracy, and the decisions he has to make about his allegiances and navigating this new place ultimately have very little to do with his growth. There’s a dating app minigame that honestly feels more tied to what Ichi’s doing in his arc than almost any of the main plotline.

Like I said, Infinite Wealth is the longest, most sprawling game in the franchise yet. There are so many delightful moments in this game, both in the main plot and outside it. I love the sequence where Ichi decides he needs to try to get Akane’s attention in case she’s just in a remote place and so they film a YouTube video essentially hoping to go viral – Ichi’s “performance” is funny and really highlights the character’s charisma. I love his relationship with Chitose, who often talks in “wiser-than-her-years” absolutes that are repeatedly struck down by Ichi’s refusal to accept the status quo. I love Kuroda’s performance of scenes where he tells people of his prognosis – they are a quiet, sad, and repetitive grief saying goodbye to a genuinely iconic character. I love all the comic relief in this game, from action movie directors to rock gods who want a thunderstorm. There is so much to commend this game – I had a blast playing it.