There are people who will tell you this was “a bad year for movies.” Those people are being lazy or incurious. I’m not sure it’s possible for there to really be a bad year for movies if you are a person who watches films from around the world, films of all budget levels, films in all genres, documentaries, animated films, etc. Even 2020, which saw COVID-19 take a sledgehammer to a schedule full of movies best seen in theaters, still saw a remarkable slate of documentaries and wonderful dramas like Let Them All Talk, Da 5 Bloods, and Steve McQueen’s Small Axe anthology.

But, no, this was not an all-star year. There are a handful of master filmmakers who released 2024 films, but those that weren’t given a limited release in January of 2025 released to pretty divisive reactions. Instead, this is more of a rebuilding year. People have been projecting doomsday at the death of the New Hollywood directors who top their lists like Spielberg, Scorsese, and Schrader. A look at this year’s best films highlights a new class of exciting filmmakers who have many years ahead of them, actors who are getting roles which unfold a new level of their talent, and an audience that is seeking out these films and beginning to take their fresh talent seriously. And these “best films” are not weaker for that fact – you just have to go looking a little deeper.

You’ll see a few Oscar players in my lineup – I also saw a few more. There is a lot I like about Anora, but I found the “driving around” portion of the film interminable and unfunny, and I think that really hampered my willingness to engage in anything more intelligent it might be trying to do. I have nothing nice to say about Emilia Perez other than that it is beaten out as the worst movie I saw last year by Aggro Dr1ft, my first theatrical walkout in a decade of logging movies on Letterboxd. The Brutalist is the latest in a sad group of movies that montage past their ostensible subject so they can be a more conventional drama about something less interesting, but I loved Daniel Blumberg’s anthem and Lol Crawley’s nighttime photography. I gotta shout out Scoot McNairy, Edward Norton and Monica Barbaro in A Complete Unknown, a movie I enjoyed mostly because a character would play a song and about a minute later someone else would join in and start playing with them midway through – they brought humanity and energy to characters that could have been so much more stock. And, of course, our future best picture winner Madame Web, whose web connects us all, was disqualified for this list because it was clearly originally released in 2003.

A hearty “see you later” to All We Imagine As Light, Between the Temples, Bird, Blitz, C’est Pas Moi, Dahomey, Exhuma, Hard Truths, Hundreds of Beavers, I’m Still Here, Kinds of Kindness, La Chimera, Look Back, Love Lies Bleeding, Maria. Nightbitch, REFORM!!!, Rebel Ridge, Riddle of Fire. Strange Darling, Stress Positions, The Bikeriders, The End, The Imaginary, The People’s Joker, The Room Next Door, and The Substance, among many others.

HONORABLE MENTION: My dad never told me I love you

Dir. Adrien Caulier

YouTube

I couldn’t quite figure out where to place this short, but I wanted to introduce people to it. I don’t personally absorb much from photo albums – maybe that’s why I admire the presentation of this complex relationship Adrien Caulier portrays in My dad never told me I love you. Caulier explores his grief in a meditative way, and the formal technique highlights an emptiness that cannot be filled by memorabilia.

24. T Blockers

Dir. Alice Maio MacKay

Shudder, VOD

A major year for trans cinema between T Blockers, I Saw the TV Glow, and my still-unseen People’s Joker and Stress Positions, T Blockers is microbudget horror about finding Nazi creeps with brain parasites and righteously beating their heads in. Even for a 75 minute movie this gets so loose you’re begging for every tangent to be some new way forward but the core charm and pissed off retaliation is so strong that it makes for a perfectly solid entertainment. I’ll be looking forward to catching up with the other horror by director Alice Maio Mackay, who seems to have developed a pipeline for making movies quickly outside a system that can say “maybe don’t make the movie about killing transphobes” and win the argument.

23. Civil War

Dir. Alex Garland

Max, VOD

In terms of base pleasures, Alex Garland’s Civil War is well acted, loud, full of ironic and high energy needledrops, and occasionally strikes a high-contrast colorful look that is visually striking. I really like Kirsten Dunst’s performance as war photographer Lee, almost as much as Stephen McKinley Henderson’s performance as the mentor who should’ve known better than to come along on the trip into enemy territory and Jesse Plemons’ one-scene performance as Sergeant Patriot Genocide. Cailee Spaeny’s solid as the naive rookie who insists on tagging along, though I probably saw more discussion of her really good pair of jeans than her performance. This film is not really an action movie or schlock, at times operating on a level of dramatic stakes I might call “ponderous.” But I’ll offer a fair warning that in terms of political satire or commentary, this has very little to say, either. If there are greater ideas on offer, they’re the self-reflexive impulse of Garland meditating on why people still see value in telling stories in a world that seems to be falling apart.

22. Only The River Flows

Dir. Wei Shujun

VOD

A small town murder mystery where the crime itself is running away from being answered, Wei Shujun is already on his fifth feature film and yet none before Only the River Flows have been seen by anyone I follow except the wonderful Ryan Swen. Our lead detective (Zhu Yilong) is being told to stop looking for the “real” killer because everyone has accepted the first suspect, and his refusal to settle is costing him so much sleep that reality and fantasy seem to be conflating. Cinematographer Zhiyuan Chengma is able to deliver a classical, sludgy 16mm look that lends with the more surreal sequences in the film’s back half, but you have to be ready to tolerate a metatext about writer’s block and trying to tell the real story even when the obvious one is right in front of you.

21. Janet Planet

Dir. Annie Baker

Max, VOD

Lacy (Zoe Ziegler,) 11 years old, bails on summer camp to go home with mom, Janet (Julianne Nicholson,) and spends the summer watching Janet fall in and out of three weird relationships. The debut film of acclaimed playwright Annie Baker, Janet Planet offers two of the best performances of the year, and watching these characters try to figure out the changes in their relationship as Lacy becomes more aware and adult is a pleasure because Baker never condescends to either character. Janet is a sometimes frustrating mother, and she’s a granola hippie in ways I find unrelatable, but she never is really positioned as negligent or disinterested – she’s loving, and when she and Lacy are talking, she’s so warm and thoughtful. And Lacy is a sometimes annoying or frustrating kid, but she’s never diminished as “a weird kid from hell,” either. Of the three relationships, my favorite is the one with Sophie Okenedo, an old friend getting out of a theater troupe/cult who doesn’t seem ready to get her life together either.

20. Hit Man

Dir. Richard Linklater

Netflix

Hit Man offers two great chapters. The first is the SNL demo reel for Glen Powell, who is playing an undercover informant disguised as the “ideal” hitman for the vengeful strangers who summon him to various diners or empty lots. It’s a ridiculous, over-the-top series of impressions and characters, and while simple, it’s very entertaining. The story arrives when Powell’s hitman job leads him toward a new girlfriend and he has to continue to play the role. Things get complicated, and when they peak in an exchange involving Notes app, this movie takes off in a sequence that must have been a thrill to write and develop. In between those two parts of the movie, Richard Linklater takes a loose, hangout approach, and it mostly settles on enjoying Glen Powell’s actual best performance in the movie as a neurotic nerd.

19. Immaculate

Dir. Michael Mohan

Hulu, VOD

Last year, I gave an honorable mention to The Pope’s Exorcist for being perfectly pleasurable before nailing the final twenty minutes. Immaculate is significantly more tense before its third act, offers some memorable and colorful imagery, and then goes just as hard in the third act. Sister Cecilia (Sydney Sweeney) joins an Italian convent and quickly finds herself pregnant – unsurprisingly, things get sinister fast. I’m sold on Sweeney, who auditioned for a failed version of this script a decade ago and bought the rights herself to make with director Michael Mohan (who previously worked with her on The Voyeurs.) I think she’s great in this, playing a balance of apprehensive fear and resignation before the scream queen horror arrives. When you throw on a random horror movie, this is basically the platonic ideal.

18. Conclave

Dir. Edward Berger

Peacock, VOD

Probably best described as “Succession with cardinals and less cussing,” Conclave is one of the most entertaining dramas of the year. That description sells it slightly short, though, as Edward Berger and cinematographer Stephane Fontaine sometimes capture high-contrast mannerist images, and Volker Bertelmann’s use of bass string plucking is a stylish evocation of older mysteries. Ralph Fiennes as Cardinal Lawrence leads a collection of expert character actors through the papal conclave election, and the twists of who’s scandalized and who’s willing to sell out are great, soapy fun.

There’s a reason the film has found its strange connection as a meme object for the queer community – its characters are archetypical, reminiscent at times of anime characterization or reality show contestants. The film finds itself somewhere between a moving, insightful grappling with the culture war within the Church – where there’s more and more tell of young reactionary priests who would prefer to cut the music and not even face the congregation, and congregations returning to women wearing the veil – and a more crowdpleasing work of liberal values showing their virtue. I have to make especial note of Sergio Castellito as Cardinal Tedesco, maybe the slimiest and most bigoted of the film’s holy men, who plays his villainy with a shit-eating grin and a puff of the Most Valuable Vape.

17. Chime

Dir. Kiyoshi Kurosawa

only being sold as an NFT but the link doesn’t even work, so just go steal the damn thing

Chime is a horror barely-a-feature with a simple premise – a cooking instructor (Mutsuo Yoshioka) is told by one of his students about their obsession with a ringing chime no one else can hear, and to his horror he starts to hear it too right before terrible things begin to happen. In forty five minutes, Japanese horror legend Kiyoshi Kurosawa (Cure, Pulse, Sweet Home) creates three or four indelible sequences with incredibly simple aesthetics, instead using solely great performances and incredible blocking. There’s a horror reaction in this that’s one of the best single acting choices in any movie this year. It’s quickly clear that even if nothing horrible has happened yet, things were off before the cameras started rolling – not knowing which pieces are going to feed back into the narrative left almost everything feeling portentous. Fair warning that this is a mystery that remains enigmatic – the lack of resolution is part of the point here, maybe reminding me of nothing more than Junji Ito’s “The Sad Tale of the Principal Post.”

16. Dune Part Two

Dir. Denis Villeneuve

Max, VOD

Dune Part Two is a marked improvement over Villeneuve’s first, with Javier Bardem getting to play a great comic relief version of Stilgar and Greig Fraser capturing a far more colorful Arrakis than before. Rebecca Ferguson, who stole the first film as Lady Jessica, hands off her expanded role to Zendaya as Chani, and Zendaya nails the repulsion when Paul Atreides takes on his role as Lisan Al-Gaib. This film would potentially make this list for the Giedi Prime sequence alone, and Austin Butler as Feyd Rautha is one of the best villain performances in years. I adored the inky-black photography, the framing of Butler and Lea Seydoux, the punctuation of Butler stumbling out “What do we do?” like a cowed child. But, I say again – I still prefer the Lynch film!

15. On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

Dir. Rungano Nyoni

Wider Release March 7th

I haven’t seen director Rungano Nyoni’s previous film, I Am Not A Witch, but I’ll have to go back after being pretty swept up by On Becoming A Guinea Fowl. The film has been misrepresented as a black comedy – it opens with a dead body in the middle of the road and a Supa Dupa Fly costume, but it becomes clear very quickly that this is a film about family trauma and sexual abuse. That isn’t to say the film doesn’t have a sense of humor – more than anything, it reminded me of Sean Baker’s Tangerine, which veers between farcical cartooning and intense emotional violence. The performances of the women in this family, especially leads Susan Chardy and Elizabeth Chisela, navigate the film’s humanist despair and its righteous anger by keeping things light and restrained, their characters talking shit, pushing the action forward, and taking moments of rest. As a study of complicity and unwillingness to confront the crimes of the dead because they loomed large in our lives, it remains an effective study of how respectability can perpetuate oppression.

14. Red Rooms

Dir. Pascal Plante

AMC+, Shudder, VOD

Red Rooms has largely been sold to me as a tech update of Videodrome, our protagonist Kelly Anne (Juliette Gariepy) following a high-profile murder trial into the dark web. This isn’t quite accurate, though – unlike Cronenberg’s films, this avoids body horror or graphic gore, instead operating almost entirely in implication and reaction. We see people watching snuff – their reactions (or lack thereof) tell us what we need to know about what we’re hearing and what we need to know about them. But the real journey is meeting Kelly Anne, whose motivation and internal life remain so distant as to transform from enigma to sociopathy, the Patrick Bateman of true crime. In some ways, this is closer to Paul Verhoeven’s Elle, where the violence’s presence as mostly verbal makes things more uncomfortable. Almost the entire film exists as a character study of this protagonist, and while there are times I felt I lost the internal logic, it’s gripping throughout.

13. Babygirl

Dir. Halina Reijn

VOD

Babygirl is arguably the most misunderstood movie of the year, with too many people watching it expecting either lurid hardcore sexuality or something coherent to say about sexuality and sociological gender roles. I don’t think it’s even really pretending to do either – Babygirl is about a sexually frustrated middle-aged executive who carries an immense amount of shame around her fetish (this isn’t a spoiler, it’s the opening and premise of the movie) and pursues it in unhealthy escapism. Nicole Kidman and Harris Dickinson both sell the lack of familiarity and comfort in their affair while also selling the pleasure and empowerment it’s bringing them – Dickinson in particular is remarkably elusive, not because it feels like he’s mysterious, just because it feels like he’s really opaque. You never know whether he’s going to get frustrated and shut down or whether he’s continuing his power play. I love the music in this movie, both the score and its weird vocalizations and the needledrops. It’s kind of vanilla, kind of shallow, but I had fun and enjoyed its character study. Even just on a camp level, I enjoyed getting to watch Kidman make the 😲 emoji face and wear beautiful outfits. I wish it ended better.

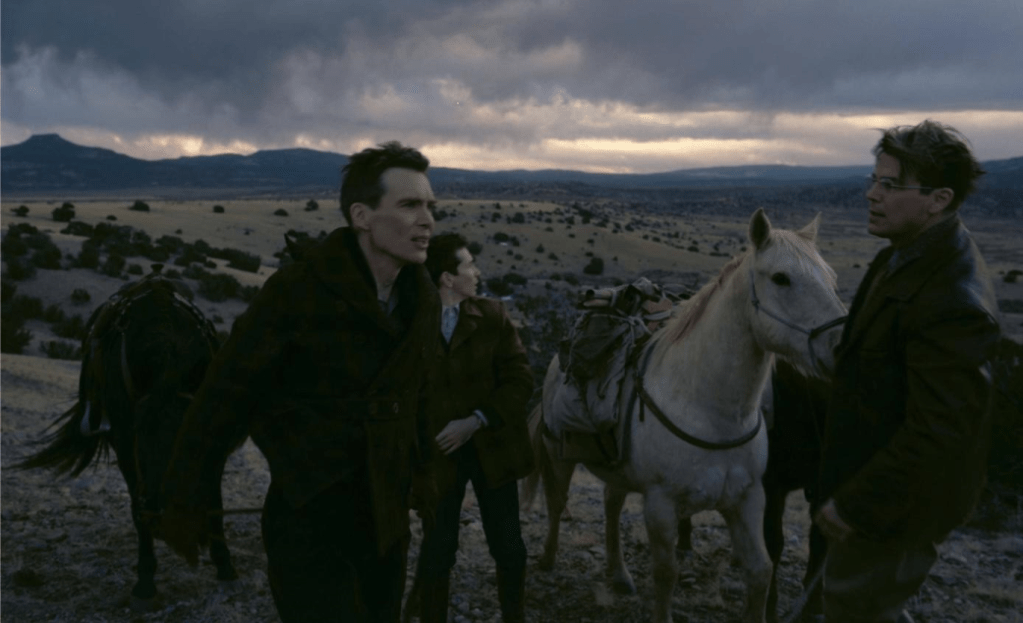

12. Queer

Dir. Luca Guadagnino

VOD

I was prepared, at some level, to separate the art from the artist with Queer, but I wasn’t expecting to have to separate the art from the other art. The William S. Burroughs novella Queer is combined here with elements of Junkie, neither of which I’ve read, but also with elements of Burroughs’ life and David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch. In Queer, Bill Lee is a gay heroin addict who becomes fixated on a young man – in most ways, Lee is an analogue for Burroughs, who briefly went by the pen name William Lee. Burroughs wrote the original manuscript of Queer while awaiting trial for the “accidental” murder of his wife in a William Tell stunt. Cronenberg brings this and other elements of Queer into his Naked Lunch – Guadagnino extends that conversation into Queer, directly lifting shots and rhythms from that film.

It is a funny, queasy, often deeply uncomfortable film. Daniel Craig is remarkable as Lee, equally terrifying and pitiable, a man who was handsome a decade prior and doesn’t know he’s too wasted to get away with being such a prick. I think the way this plays out as a film about what happens when we chase queerness back into the dark and allow old creeps to be our guides through this world is just as relevant as it was in the gentler Call Me By Your Name. Jason Schwartzman is remarkably funny as a furry little hobbit of a man who also gets far more play than Craig’s Lee. If this film is lower than the sum of its parts, it’s because I really hated the epilogue, which drove the links to Burroughs and Naked Lunch too far for me.

Perhaps the most frustrating casualty of the strikes of ‘23 sliding the slate forward, Challengers and Queer deserved their own distinct awards runs by the brilliant team director Luca Guadagnino has assembled. Like Challengers, I love the screenplay written by Justin Kuritzkes, who is sharply funny, so elegant at drawing distinctive characters, and is careful with withholding information. I love the cinematography by Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, the genius who shot my previously beloved Beckett and Memoria (as well as Challengers and Trap this year!), whose visual language creates a dreamlike city of expats living in lush, painterly light. I love the costumes by Jonathan Anderson, who in both Challengers and Queer creates distinctive modern wardrobes that both feel immediately recognizable and also visually iconic. I love the music by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, working in a subtler mode compared to their Challengers score, but one that helps create the intense loneliness of Bill Lee’s exile.

11. ME

Dir. Don Hertzfeldt

Vimeo

I’m not sure when I was a teenager watching Rejected on YouTube that Don Hertzfeldt would become, almost inarguably, America’s greatest working animator two decades later. Between his feature film It’s Such a Beautiful Day and the wonderful World of Tomorrow trilogy of shorts, he’s demonstrated incomparable insight into generational trauma, the ever-warping detachment of memory, and the increasingly isolated modern world. ME takes these themes and applies them to a musical short film, replacing his often very poignant dialogue with the pulsing beat of Brent Lewis’s Drumsex and classical aria. That doesn’t leave ME too abstract – rather, it’s maybe the most straightforwardly funny film and directly political he’s made since his film school work. I don’t want to spoil what happens – Hertzfeldt’s own advertising for the film is deservedly enigmatic – but I can say that Hertzfeldt’s animation has rarely been more expressive or better edited.

10. A Different Man

Dir. Aaron Schimberg

Max, VOD

A film which threatens to be too clean and manages to disorient over and over again, Schimberg’s A Different Man offers a New York City that feels disjointed from time entirely. Sebastian Stan’s Edward lives in a shitty apartment when he’s not starring in altogether awful ads, the limit of the work he can get with his advanced neurofibromatosis between frequent surgeries. Miserable, he receives an opportunity to pursue a miracle cure right as he falls in love with his new neighbor (Renate Reinsve) – when the cure works, he takes a new lease on life, only to meet another man with the same condition that lives the life he wishes he had all along.

Working with a sense of humor that bounces between the irony of Dostoevsky and the simple pleasure of a good Simpsons episode, this is the funniest movie I’ve seen this year. A Different Man navigates heftier subject matter like representation and ableism with a willingness to go for the joke and yet always maintains its tension. The Umberto Smirelli score and Anna Kathleen production design maintain a sinister undercurrent to Edward’s machinations. I’ve never seen Stan better playing both the empathetic frustration of Edward’s emotions without any ego about the dark and often stupid places the character goes. And Adam Pearson has rightfully become the centerpiece of discussion of this film, an instantly charming socialite who is also constantly one-upping Edward at every turn.

9. The Beast

Dir. Bertrand Bonello

Criterion Channel, VOD

If you need one more dollop of the Lynchian to cap off your mourning of film’s greatest dreamer, Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast contains an overt love letter to Lynch’s style. Bonello begins The Beast as an adaptation of Henry James novella The Beast in the Jungle with a science fiction frame, and in that it is a gorgeous, sincere, tragic story of someone whose existential dread has swallowed their dream of love and happiness. The gauzy camerawork gives these scenes the soft lighting of rococo, and the production design of this sequence is rich. Lea Seydoux plays her usually catlike coldness, unknowable but alluring, and if you’ve not seen her in a film before, it tells you everything you need to know about her persona.

But in his next trick, Bonello transposes that story out of time and reincarnates it in Los Angeles, resurrecting elements of Lost Highway, Mulholland Dr., and Twin Peaks The Return to set the lead lovers at odds. The two leads, Seydoux and George MacKay, are two of the best performances of the year, communicating so much with posture and expression that their characters are afraid to say aloud. And yet most impressive is the way Seydoux plays the relative comfort of that Los Angeles storyline, logically aware something is off but emotionally unguarded from whatever that might mean.

At some level, this is the most frustrating film for me in this top ten, because it gets a little too cute with its homages and its metaphors and at times drowns itself in pastiche. When it’s working, it is one of the more profound and beautiful films of the year. I hope I grow to love it even more over time.

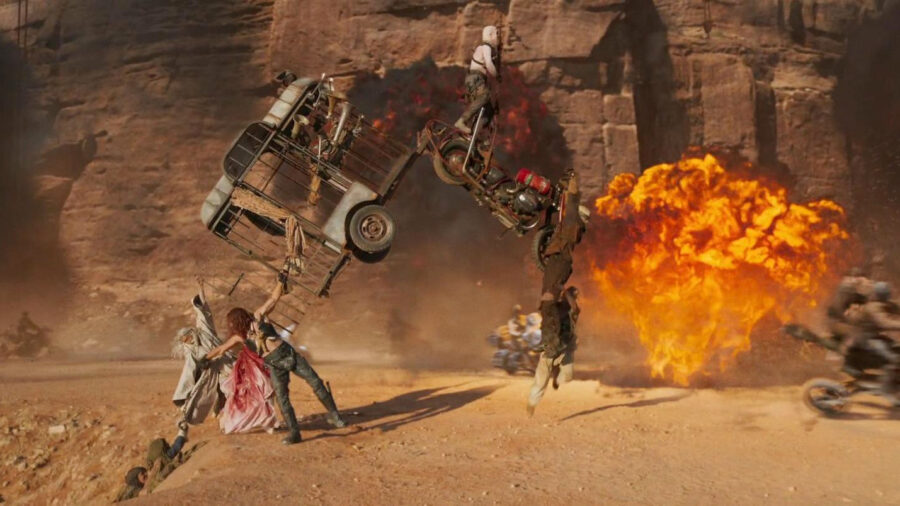

8. Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

Dir. George Miller

Max, VOD

[this is an abridged version of a longer piece i’d drafted about Furiosa and was never quite happy with. Hopefully, it entertains you now.]

Furiosa is a fun action film full of bewildering stunts and perfectly choreographed action sequences, unbelievable color underneath revving engines and fiery explosions, and Chris Hemsworth as Dementus devours the whole hock of ham. I enjoyed watching Anya Taylor Joy in the role despite not thinking Furiosa is all that strong a character – I appreciate the way the film shows Furiosa as a resourceful survivor from the beginning of her journey, always looking for the best path to her goals rather than that being a response to her life in Immortan Joe’s Citadel.

The merits of the film are both somewhat self-explanatory on the screen and hard to discuss without watching multiple times. Instead, what I want to talk about is Furiosa’s wasteland. Fair warning that this will contain spoilers for the film, though I doubt anything I say will spoil the experience.

Furiosa starts us in The Green Place, a place of abundance. We see men in The Green Place’s town, we see horseback riders, and we see wind turbines. In Fury Road, The Green Place has become the stilt-walker swamp. It’s hard to imagine scavengers not finding them more often. The scavengers we do see, Toejam (David Field) and his gang, ride to Dementus’s tent camp. That tent camp eventually rides to round up other scavengers, including the torture game we see in the gang battle that recruits Mr. Norton (Elsa Pataky’s second role.) Tent camps are not considered civilization – when we return to Fury Road’s trifecta of The Citadel, Gastown and the Bullet Farm, there is “nothing else out there.”

And this world is defined by vehicles driving at relatively high speeds. Even being relatively conservative, the V8s and rigs likely drive around 45 miles per hour across hard desert (metric, that’s roughly 72 kmh.) East to west, that leaves modern Australia roughly 55 hours across – keep in mind that the oceans are not what they were. In describing her journey to Praetorian Jack (Tom Burke,) Furiosa states they’ll drive three days east from the Bullet Farm, and then “take the bikes the rest of the way.” This is far enough that The Citadel, Gastown, and the Bullet Farm don’t find The Green Place.

Either they’re right that nothing else is out there, it’s too expensive to explore that far out safely, or they found The Citadel and are encouraging those in their circle to stay within the world The Three Fortresses create. The Three Fortresses operate on barter economy – rigs drive between (including that of Praetorian Jack) and deliver food from The Citadel, guzzoline from Gastown, and ammo/weaponry from the Bullet Farm. We don’t get a ton of visibility into life as a warboy, even while Furiosa is in disguise. “Witness” is the primary reward structure – valiance potentially leading to promotion within the ranks.

When I isolate how this world works economically – how it creates this system of trade and political control by Immortan Joe and his designated allies – it starts to become clearer how this world’s design operates and the story it’s telling. The world of Fury Road and Furiosa is one where control of resources and information control are one and the same. Dementus never gives away to Immortan Joe that The Green Place exists, and Furiosa only shares that knowledge with Praetorian Jack. But pursuit of other territory is never part of Joe’s goals. Joe is portrayed as a rapacious and tyrannical fascist, with his domination focusing primarily on the brides and his warboys.

Some post-apocalyptic stories, like the Fallout games or Stephen King’s The Stand, operate as colonial resets. The political allegiances have been obliterated, and unincorporated territory is open again for reclamation. Wars play out between factions seeking to claim control. The “evil” faction is the one that allows subjugation, debauchery, or enslavement. The “good” faction usually seeks to reinstate the status quo of liberal democracy, or maybe create a small sense of collectivism. In Zardoz, we see a world where the subjugators reshape the world in their service, their tabernacle separating immortals from the “brutals” farming and cultivating resources. Others offer an Eden – find the Green Place, save your people.

Furiosa, and Mad Max Fury Road, don’t really operate that way. The story is not about returning to The Green Place because Furiosa wants to claim it for her people. Furiosa’s initial drive is about returning to family and virtue for the individual. Her journey is about learning that the evil subjugators who have removed her from a paradise have actually earned the vengeance she wreaks upon them; and, she learns that their victims merit consideration. This film tells a story about learning to tend to your own neighbors, even in a homeland you despise, rather than solely serving oneself.

We are in a time of global political turmoil. Rising far-right fascism, theological or purely narcissistic, surrounds us on every continent. People I admire are once again scanning for emigration, trying to find places where social movements are at least moving in the right direction. With the prior film, Fury Road, the story may have told a fairly surface-level “fuck you” to misogynist slavers and fascist cults of personality, considered the idea that we might be too late to return to paradise, and relished in a conclusion that asked us to consider the ideal life in a broken world. Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga pulls the myth back and begs us to recognize the sacrifice our epic hero makes, her monomaniacal escape drive kicking back toward empathy and real heroism to protect the victims of evil.

7. Trap

Dir. M. Night Shyamalan

Max, VOD

The most perfectly designed of Shyamalan’s films since The Sixth Sense, Trap is a wildly entertaining identity game. The Butcher (Josh Hartnett), that freaking nutjob that goes around chopping people up, is taking his daughter to a tween pop concert, and the feds know The Butcher is there and have turned the whole concert into a trap. Watching Hartnett assess the extent of his opposition while a pretty realistic depiction of a C-list pop concert happens in the background is pure candy, and the sudden outburst of violence or jokes at Hartnett’s corny dad persona are equally blissful. Sayombhu Mukdeeprom’s stellar year never made me laugh harder with a camera movement than a pivot to a piano in the film’s second act.

But then on top of all that, this is a film with so much to pull apart, from meditations on fatherhood, ostracism, depersonalization, the validity of anger, and structural choices that inform our opinions on fame, policing, pathetic violence. It operates on a meta-level of Shyamalan working with his daughter Saleka, who plays the pop star Lady Raven in the film, and asking questions about how family and “personal projects” are ethically kept separate. (On that note, I also think Saleka’s performance has been wrongly dismissed – I think she’s believable as a stage kid, and her music is believable for the kind of audience she attracts!) It’s both as fleshed out and as entertaining a film as he’s ever made. After the last three, I think he’s really reclaimed his title as a master filmmaker.

6. Evil Does Not Exist

Dir. Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Criterion Channel, VOD

Since I last wrote about Ryusuke Hamaguchi when he took the top slot on my top 21 of 2021 with Drive My Car, he’s only grown in my estimation as a storyteller. His prior films, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, Happy Hour, and Asako I & II all solidified his mastery for stories of mistaken identity, complicated friendships, and people aspiring for profundity when play would have been more socially acceptable. Evil Does Not Exist largely eschews Hamaguchi’s comforts in art and artists. It is, instead, a film about gentrification and its threat to a small rural town, with a talent agency trying to lay claim to a COVID-era development grant and build a glamping site. The flashy urbanites are set instead as the outsiders looking to displace our heroes’ way of life, even if the agents sent to negotiate the development are well meaning. Hamaguchi and the cast treat both the locals and these agents with love and humor, recognizing when they are being difficult or manipulative without diminishing their empathy.

But perhaps his biggest departure is in tone and presentation. This is a film with long periods of quiet, originally conceived as a silent companion to Eiko Ishibashi’s gorgeous score, where you watch tasks like chopping wood or collecting spring water. The most dramatic scene in the first half of the film is a town hall meeting discussing the glamping site, one which recalls similar “confrontations” in films like Frederick Wiseman’s City Hall more than traditional drama. But when the stakes raise in the film’s climax, there was something terrifying and desperate that Hamaguchi has not tapped into elsewhere, and the title’s ominous and confrontational title takes shape in a way I’ve been wrestling with all year.

5. Nosferatu

Dir. Robert Eggers

Peacock, VOD

The most baffling response I’ve seen people have to Nosferatu is to dismiss it as a “technical exercise.” I think it’s because I know Eggers’ history – that Nosferatu is his longest running passion project, that he adapted it for the stage in high school, that that play became his first professional production at the Edwin Booth Theater in New York in 2001, that he was going to make this film after The VVitch if The Lighthouse hadn’t taken precedence. The exacting control over this film’s visual language isn’t dispassion or validation – it’s decades of monomania come to fruition. Eggers is the historical reader’s ideal filmmaker. His desire to play with tropes and familiar subjects and return them to the culture from which they sprung reminds me so much of discussions with two of my favorite instructors Jeffrey Steele and Ron Harris, who shared their love of Herman Melville and Christopher Marlowe while refusing to mythologize them as unrelatable or inhuman.

But, even setting aside motivation, I simply think Eggers made a thrilling and gorgeous film. I can’t sing the praises of every performance without making this altogether too long, but I agree that Lily Rose Depp and Bill Skarsgard should be taken as especially remarkable for their portrayals of Ellen Hutter and Count Orlok. Their approaches to those characters are so remarkable both in their physicality and their voices, and I especially think they compare favorably to Winona Ryder and Gary Oldman in Coppola’s adaptation of Dracula. Unlike that film, there is no romance to Eggers’ fated – they are doomed to one another, and the “appetite” Orlok identifies is one of despair and plague. It’s real monster shit, and it fucking rocks.

4. Megalopolis

Dir. Francis Ford Coppola

Pending Rerelease

I have tried a couple times to write about Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis and I keep getting stumped. I keep attempting to describe what the movie is, which is best answered by watching the movie, and not why I care. People who know my film taste probably recognize my propensity for audacious, colossal epics that others might describe as “a money pit of terrible ideas executed terribly,” “a deranged freak-fantasia,” “a personal vision writ extremely large,” or “a glittering cultural trash pile.” I find these films often challenge the preconceived notions we have about storytelling, adventuring into a selfhood that no one can quite replicate, and many can’t enjoy without the remove of “camp” to offer guard against the life-altering substance at the film’s core. Sometimes, I’m lucky enough to see these films reclaimed by a larger cultural movement. But I’m also okay maintaining my small community of like-minded jellicles who keep the concept of a cult film alive.

At the expense of other details, I must highlight the performances. Adam Driver as architect, city planner, and artist Cesar Catalina is able to wring a charismatic, compelling presence out of an impossible character. Catalina’s motivations and ego are constantly in a storm, and he veers wildly between theatrical monologues (his first contains the entirety of Hamlet’s famous “To be or not to be”) and monotonous deflection. It is solely through Driver’s hand that this becomes a character we understand and care for. Aubrey Plaza is his closest match as the venal and lusty Wow Platinum, really leaning into the comedy of her character’s femme fatale role and heightening the work of everyone around her. I enjoy almost everyone else – Jason Schwartzman in particular gets two of my biggest laughs of the year – but those are the two I consider really especially remarkable.

Let’s talk about Megalon.

Megalon is the liquid metal unobtanium Cesar Catalina has synthesized to construct Megalopolis, his utopian project. It’s unclear exactly what Megalon is made from, if it requires the harvesting of some raw material, if it has any definitive physical properties. At one point, Cesar divulges how he came across the core of Megalon in mourning his suicidal wife, a woman he’s suspected of having murdered and – despite his “innocence” – blames himself for killing. Megalon is pure inspiration – it is galvanized imagination fired by dissatisfaction, grief, guilt, and mania.

This sort of broad, literalized emotion makes Megalopolis one of the year’s most vital films. In a bravura sequence at the beginning of the film’s second act, Driver’s Cesar plays the drunken fool for the paparazzi and falls into a near-catatonic fantasia of self-indulgence. The editing rhythms that take over for this scene are energizing and hypnotic, while Cesar’s world is falling apart in the gladiatorial arena. It works on an ecstatic emotional level, battering you with broad comedy, sex, drugs, garish CGI, bizarre line readings, and deeply sincere half-statements about believing in a better future.

In text, Megalopolis does not argue well for itself. I mean, it’s very entertaining, with most of the viral moments being very intentional jokes. It’s often visually striking in the same way as 2000s CG can be, reminiscent of the Star Wars prequels, Southland Tales, and Spy Kids 2: The Island of Lost Dreams. Every five minutes, you will go, “Wait, what the fuck, did that really just happen?,” only for the next five minutes to surprise you yet again. It is a somewhat exhausting rollercoaster ride you will not soon forget.

But in trying to assess what it all builds toward, I can only offer the generosity that the now-elderly Coppola recognizes he does not have the answer to utopia. He is a conflicted, bitter, old man who tried to make his own movie studio where the safety and conservative values of the major Hollywood slates had no reach – he was destroyed almost immediately, and watched as those who reflected his own values were destroyed along with him in favor of Reaganism and neoliberalism. He cannot envision the way forward – Megalopolis is his plaintive cry that somebody at least continue to ask the right questions.

3. Nickel Boys

Dir. RaMell Ross

MGM+, VOD

In the purest argument of representing an evolution of film as a medium, nothing makes as clear an argument as RaMell Ross’s Nickel Boys, an adaptation of the Colson Whitehead novel about exploitation at an abusive reform school. The film utilizes a remarkable first person perspective, taking the point of view of protagonists Elwood (Ethan Herisse) and Turner (Brandon Wilson), a technique usually restricted to individual scenes or found footage films like The Blair Witch Project. This is a radical choice in adaptation – the novel is told in third person, and its prologue lays out the nature and degree of evil the characters will face at Nickel Academy. It is so long before we first see Elwood’s face, and when we finally do, we realize how other people perceive this character’s energy, a little off putting, a little vulnerable, a little sad.

Then Nickel Boys starts taking advantage of these two perspective characters to disorient us further – we start seeing dreams, scenes of waking up in the middle of the night, entering a room and not knowing whose eyes we’re in. This feeling of not knowing what character perspective we’re in would simply not be possible without this perspective. It is similar to how I discussed Game of the Year 1000xResist, which also uses its core premise to tell a story in a way that would not work another way. In an early scene where Elwood’s grandmother (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor, in the year’s best true supporting performance) visits Nickel, we’re excited for a moment only before we realize we’re in Turner’s head, and Elwood is not allowed to see her. Their scene together is intimate, uncomfortable, and devastatingly sad, and it takes on extra intimacy and potency because of the formal technique that anchors it.

Nickel Boys does not linger in violence or its peak moments of trauma. I think Ross recognizes that this point of view could heighten this film into new extremity, into misery pornography, into a radical provocation of how important it is not to look away from racial violence. But I think, structurally, Ross instead highlights the characters in moments of hope or connection – sometimes, that hope is deflated in the very same scene. Our protagonists observe a moment where a friend’s dream of athletic victory is ripped away from him – just before that, they’re telling one another about their families, Elwood’s copy of a Jane Austin novel, what life should be. It cares about these characters, and caring about them is showing them outside of just instrumentalizing their trauma.

The technique is hardly the only wonderful thing about this film. All the performances are uniformly excellent. The film, while covering exploitation, makes space for joy and community, and it does so by celebrating life that cannot be extinguished rather than by romanticizing their circumstances. Ross uses his history as a photojournalist and documentarian (he previously directed Hale County This Morning This Evening) to create sequences of gorgeous imagery that might feel indulgent if they were not so gorgeous or personally resonant. It is rare to see a film simultaneously do something so experimental and also nail every classical element alongside it. Ross has instantly declared himself a filmmaker of importance – Nickel Boys will survive regardless of how first person perspective evolves because it tells its story with confidence and care.

2. Challengers

Dir. Luca Guadagnino

Prime Video, VOD

Even better than I gave it credit for being, I had been underrating the film as almost hermetically sealed, but there are other characters who arrive for a spotlight scene outside our main trio. Burgess Byrd is so funny as the woman in New Rochelle with the Dunkin’ Donuts, a little starstruck because she remembers Patrick from his junior doubles match with Art. Christine Dye is as good as the hotel clerk Patrick tries to sleaze for a room – ditto for Hailey Gates as the real estate agent trying to maintain enthusiasm for Patrick’s tennis career despite just wanting to bone down. But everyone’s there to serve Tashi, Art and Patrick, and it’s their relationships that are just perfectly tuned throughout. Kuritzkes really proved himself this year as having an incredible sense of character between Challengers and Queer – I’m so excited that the Potion Seller guy has become a brilliant screenwriter – he’s already got three more projects lined up, and I can’t wait to see any of the three.

I ended up getting to see Challengers again as part of Annie’s birthday celebration this year, and perhaps the greatest treat of Challengers is realizing that every single scene is another “oh, right, This Part!” scene. When match point arrived and the fireworks started going off, I started crying from an ecstatic sense of delight, not wanting the film to ever end. There is nothing in cinema this year that matches the finale’s pleasure, its perfect storytelling, its audacious technique, the delightful “Match Point” track by Reznor & Ross. The final shot hit, the final cry erupted. The credits rolled, I leaned back, and I wanted a cigarette.

1. I Saw the TV Glow

Dir. Jane Schoenbrun

Max, VOD

This is an instant all-time favorite. It has left an insurmountable impact on my life. In a time when I feel more exhausted than ever before by a desperate world, I take strength from Maddy begging us to love ourselves enough to be willing to give up the sludge and be authentic. I have been trying to find a post for a while now, from maybe a decade ago. It declared that when queer people come out as queer, they must understand that their family, their community, their government may reject them – they are fugitives existing outside of the status quo. This can ultimately be taken as inspiring, that every queer hero you’ve ever had survived to change your life, but it does not invalidate the real violence and abandonment queer people have experienced, either. This film grapples with that violence and what it means to be a fugitive and thrive as your true self.

The feelings I have toward I Saw the TV Glow remain so intense that I have a hard time thinking about this film without getting emotional all over again. I want to say thank you to my friends who have heard me talk about the film and watched me choke up again without razzing me about it. I want to thank Jack Haven, who I did not make a lot of space talking about in my original piece and whose words ring back in my head as rejoinders to remain inspired rather than afraid, and whose social media presence is just so fucking cool. I want to thank Jane Schoenbrun for coming up with a language that I find so essential in understanding my own experiences, the way Jordan Peele added to the lexicon with “the sunken place” and “third term Obama voters.” And I want to say thank you to Annie, who has been so profoundly loving when I talk about encountering waves of not knowing how to dress, how to present, how to feel like myself.

Don’t apologize.