Lynch was not a filmmaker first. He’d gone to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts as a painter, and only began filmmaking out of a desire to see his paintings move. His first “films,” Six Figures Getting Sick and The Alphabet, are mixed media exhibitions that, even after the rest of his strange and wonderful career, come across more as museum pieces than cinema. Six Figures Getting Sick, notably, was originally presented on a sculpture “screen,” complete with plaster heads bubbling out of it. Working contemporary to Warhol and the evolution of video art, Lynch diverted from that path with the AFI funded The Grandmother, which signalled many of his anxieties, thematic concerns, and stylistic flourishes from the very start.

But my favorite of these early shorts is actually The Amputee, a two minute film (with two different takes, on two different filmstocks) in which an older woman writes an opaque letter about a convoluted series of relationships. It’s a very simple, one shot film, where the titular amputee is played by Catherine Coulson, better known as Twin Peaks’s Log Lady. Coulson was working behind the scenes on Eraserhead when they decided to shoot The Amputee as a film test – she’d been brought on board with her husband Jack Nance, though they divorced before Eraserhead debuted. This short, to me, is emblematic of the way Lynch works with fellow artists, takes these little diversions, and discovers something magical. While Eraserhead is this moral shock, this exorcism of Lynch’s demons around city life and the family unit, it’s The Amputee that paints the way forward as an empathetic look at the frustrations of internal life and the gaps between people.

Lynch described himself as an absent husband and father, saying himself in Room to Dream that “film would still come first.” The safest way to stay in Lynch’s life was to be an artistic collaborator first and a friend or lover second. His loyalty to Coulson and Nance was lifelong – perhaps the most profound moment of David Lynch’s final mainstream work, Twin Peaks: The Return, is Coulson as The Log Lady, eulogizing herself. Her words come to me regularly, reminding me “about death – that it’s just change, not an end,” words that I’ll be thinking about for many days to come. Kyle MacLachlan, Laura Dern, Naomi Watts, Grace Zabriskie, Sherilyn Fenn, they all joined Lynch’s repertory family. Jack Fisk, Angelo Badalamenti, and Mary Sweeney, among many others, were collaborators over several decades. When he became largely homebound with his emphysema, sometimes the greatest collaborator was his own family.

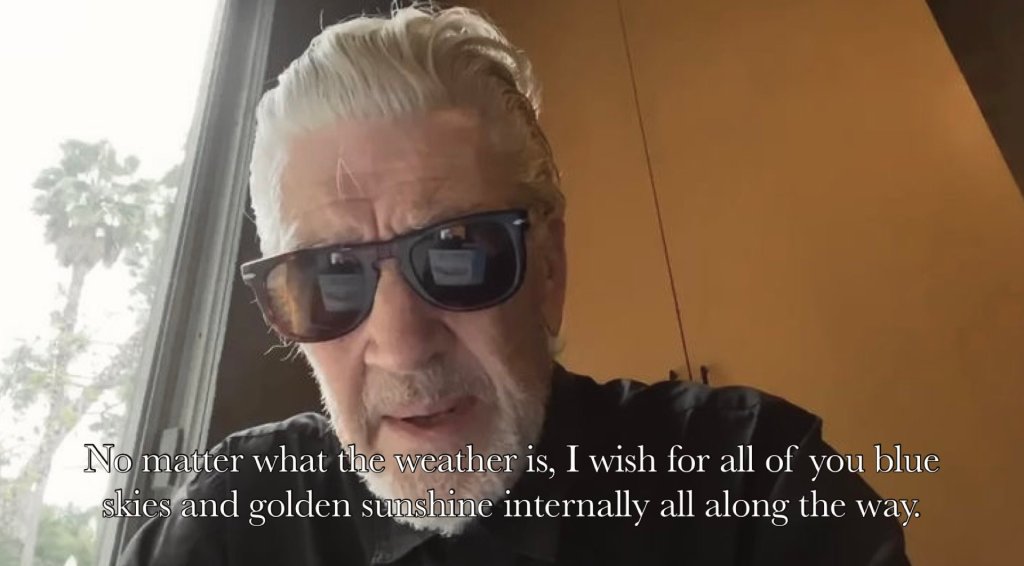

One of the greatest things about David Lynch was that, so long as the art was not “taken away from him,” he did not consider any of his artistic endeavors unworthy of love and attention. When David Lynch fell in love with Flash animation, he made Dumbland, which is not some intellectual exercise but is just as puerile and funny as anything on ebaumsworld or Newgrounds. When David Lynch made a barn for his daughter, he shared it with the world. When David Lynch did daily weather reports, he did it with pride, and when he had to stop, he did so apologetically because he knew they brought people joy. Some people voiced frustration with David highlighting an announcement only for it to be more experimental music with Chrystabell – but it’s his love for all this creation that made him the man who never thought twice about taking the personal path.

I don’t want to catalog what the films and Twin Peaks mean to me right now – I’d like to give them all the space they deserve, each a treasure worthy of being unpacked on its own, each not painting the full picture of who this man is to me. I named my newsletter The Horizon Line after his final on-screen appearance as John Ford in Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans. As I shared in my Blue Velvet piece, Lynch’s work is at the heart of so many of the relationships I have in my life. He is at the fundament of my worldview and identity, my belief in a person’s ability to grow, my belief that the inexplicable can also be human. Like many, every time he made a public statement or new work of any kind, I was happy to hear his voice again. I’ll miss him so dearly.