THE TREE OF LIFE

Dir. Terrence Malick

2011

I vaguely referenced The Tree of Life’s ending in my piece on Malick’s Days of Heaven, noting that extended denouement is how Malick allows the film’s story to end without closing off its emotional impact. I’d forgotten, then, that after the beach scene, that this film ends as it begins – in the dark, looking at unknown divine light. Loving The Tree of Life requires patience, as it is a film that repeats itself often, reflects on a single idea many times, and does so in poetic language and straightforward symbols. These work for me because they are real – both in that they are personal, often reflecting elements of Malick’s own life, but also because they are the kind of symbols people attach to in real life, a little pat and in a way that feels like they handwave specificity, but then in refinement the specificity emerges once again.

Look – it’s that kind of movie, it’s gonna be that kind of write-up. Some critic, I can’t place where I read it, wrote a story about meeting a truck driver who watched Yasujiro Ozu movies with his mother every Sunday. The story served as a warning against condescending to audiences, assuming “art films” were inaccessible to the masses and aren’t based in relatable everyday struggles. The Tree of Life is certainly relatable – it’s a story about fundamental questions about the Christian problems of evil, about class, about wrestling between your parents’ ideologies, about grief, and about coming of age. It’s not Godard’s abstraction, which demands familiarity with Brecht and Derrida and Marx in an essay film.

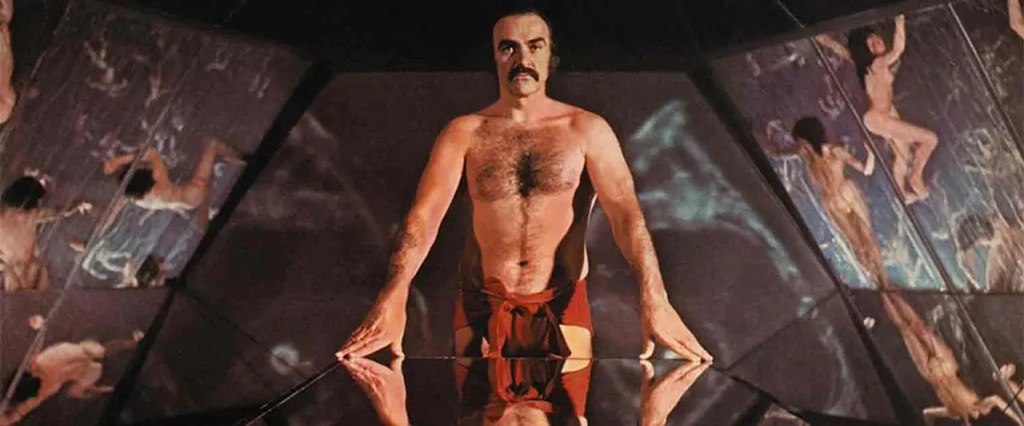

Any viewer is smart enough to get The Tree of Life. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to land with everyone. This nonlinear story about a boy named Jack O’Brien (Hunter McCracken, also Sean Penn) and his family, the later untimely death of his brother R.L. (Laramie Eppler), and Jack’s later adulthood malaise is interspersed with landscape photography and a CGI telling of the origin of life. It is, to say the least, light on action. Most of the story is based in Jack’s coming of age, which involves him reckoning with an increased assignment of duty by his hot tempered father (Brad Pitt,) concern for the temptation of evil, and burgeoning sexual desire. Malick warns against considering it autobiographical, but if the film is not filled with events from his own childhood, it is based in a lived reality of this community. A scene only in the extended edition takes place at Malick’s childhood boarding school.

Most of the internal emotion is told in soft spoken monologues. Many of these monologues are very blunt – the film’s most famous line of dialogue is Jack opining, “Father. Mother. Always you wrestle inside me. Always you will.” The characters are almost overly expressive with one another, with Chastain’s face of disappointment or concern as Jack slams doors or stomps around a mask of performative distress – it’s hard to tell if she’s really so wounded by his turmoil or if she’s affecting a silent reproach until he’s willing to soften. McCracken holds his own in these monologues against Pitt and Chastain – it never quite has the lived in reality of Linda Manz in Days of Heaven, but this is a more heightened film anyway.

I previously thought Pitt’s turn as Jack’s father was Pitt’s career best performance, full of locked down rage and resentment that erupts violently and only settled upon working with music or machines. I still think it’s great work. Father over the course of the film is shown to have such a limited emotional range that it’s hard to compare it against his charisma nukes in films like Fight Club or Moneyball. He continuously states that being too soft, too virtuous is liable to get you walked over in this world – he characterizes his demanding expectations and swift physical reprimand as making sure his sons know how to be independent and get what they’re owed. He offers this wisdom as the law of nature, tough but rewarding. It’s challenging to watch him become the holy terror of this household, the children openly celebrating when he goes away on a trip, knowing what Pitt is like with his own children.

Meanwhile, Mother is stationed as serene grace, the vision of tolerance and gratitude, and represents the argument that the virtuous and generous lack for nothing. The film complicates this in a few ways – first, the death of R.L. exposes her naïveté in believing virtue is the shield of God. Secondly, her tolerance of Father’s abuse and failure to equip her kids to protect themselves from him lends credence to his argument, that you do have to be able to fight back to protect virtue to begin with. This is ultimately the spiritual debate this film is engaged in – crusade vs. tolerance, Nature and Grace. My wife framed it as understanding the two sides of Christ, the cleansing of the temple vs the forgiveness of the cross. Sometimes, I feel the depiction of the parents goes a little broad to suit this paradigm – while it’s aesthetically beautiful, I forgive anyone who rolls their eyes at the dream of Chastain flying among the wildlife like a Disney princess.

Nature and Grace are each given monologues. Nature’s is actually given by Chastain, shortly after wondering “Why did my son die?” She delivers this monologue while we watch a scientific depiction of the birth of the universe, the beginning of life, and the age of the dinosaurs. For a film this explicitly about religion, this non-creationist genesis takes on the argument for intelligent design. We see two dinosaurs fight, as Jack and R.L. will, and see one of them spare the other after stepping on its neck, assured it is not a threat. Soon after, the asteroid strikes and the age of man will begin.

Jack’s coming of age also includes the arrival of his sexuality, and the transference of an Oedipal awakening onto a neighbor. We follow Jack on voyeuristic trips to peep through windows, and when the house is empty, he goes a step further. While it often can feel that sexual awakening stories are incidental in a greater neighborhood, this one feels instructive both thematically and aesthetically. It personalizes and isolates Jack’s grappling with sin – he can tell his Mother about vandalism or a scary encounter with other boys blowing up a frog with fireworks, but he can’t tell her about these feelings.

Lubezki and Malick’s camera is constantly in motion, and the blocking of actors and composition of shots is constantly creating interesting lines of motion. The moment one aspect of a space is obscured by a wall, a tree, or a camera movement, another detail opens up. It is inventing new beautiful images so frequently that it can be overwhelming. I would describe their work as aiming to give the viewer the eyes of a child, awestruck by every new thing in sight, teaching them ways to look for a divine, aesthetic beauty in every day situations. This is the purpose of the film’s approach to landscape photography, with canyon walls curling to reveal the beauty of natural law, mathematical reality creating beautiful, astonishing shapes and patterns. It uses this same eye on factories, churches, and houses, revealing the way mankind has imitated this mathematical vision. In Lubezki’s cinematography and Malick’s direction, I can see God.

But the pleasure of looking past the trees to see the sun behind, even more beautiful, is framed by Jack’s sexual awakening as the same pleasure one gets looking through a window at an undressing neighbor. Malick seemingly indicts the same divine vision he’s offered us, perhaps a warning against the overtuned eye. I don’t think so, though – I think he is more just acknowledging the reality of receiving this gift of sight, that it will bring great joy but also tempt the voyeur. It is an aesthetic battle between the appreciation of the world and the aggregation of its spoils.

To put it bluntly, while I think this is a valuable spiritual conversation, I also think this is one hell of a Boy Movie. It does not really make much effort to fully take Mother’s perspective, and it offers us no other women’s interiority barring one barbed conversation between Chastain and Fiona Shaw, the boys’ grandmother. Like a lot of texts grappling with Christianity, it depicts women only in maternity and lust. Its understanding of gender is based in a version of complementarianism, and it is about as rigid a binary as imaginable.

It’s not like I expect a 68 year old Malick to be busting the binary back in 2011, and I don’t consider it a “flaw” of the movie. Rather, the film’s somewhat limited masculine perspective is instructive, a modern contextualization of spiritual debates that began when women were, as far as the Catholic church was concerned, dehumanized. It uses gender largely as a representation of a spiritual debate – and yet, internal struggle about that debate is more largely offered to men.

If you were not engaged in this film’s spiritual debate, and were not as aesthetically awestruck as I am throughout its generous runtime, I’d hardly fail you for not relishing the film’s climax, a vision by Penn’s older Jack at Revelation, the dead returning to life at the shallow sea. Jack reads to us the argument for Grace here, Penn bringing us to a culmination. At the end of the world, we will be reunited with everyone we ever loved, whether that is our dead brother or the boy who was burned in a house fire that one special summer. We will embrace and we will give ourselves to God. I find it a simple ending – I find it a profound ending.

I do not have the entire film codexed. Hell, my non-religious ass is missing major context and references to scripture. The nuances of the film’s uses of classical music are largely lost on me, too. It’s a film I expect to get more from every five or ten years. But if nothing else, I’ll always be entranced by that gliding camera, whether moving through Penn’s modern apartment or up the titular Tree of Life itself.