Animal Well

Billy Basso

NS, PS5, XSX, PC

The insular popularity of Fez, your favorite game designer’s favorite game, has haunted me for twelve years. Designed primarily by infamous director Phil Fish and Renaud Bedard, the puzzle platforming of Fez dominates the cosmos of Animal Well, which trades Fez’s tone of post-Vonnegut observational comedy for a lonely, haunted malevolence. Instead of the hypercube tearing the cosmos into black holes, instead some dark, spiritual energy sends malevolence into the already carnivorous world of Animal Well. Your little blob darts into the remains of somewhere obviously forgotten.

Structurally, Animal Well has much in common with Metroid or Zelda, though it lacks either of their focus on combat. A 2D exploration platformer with a map so dense you’ll eventually fill all but the barest walls, your simple leap helps traverse abstract non-places filled with creatures and critters dangerous and benign. You navigate puzzles across four animal kingdoms, collecting tools which help you delve deeper into these mazes. My favorites of these are the yo-yo, which can hit switches down pits and around corners as it rolls on its string, and the thrown disc, which is sometimes a frisbee you throw or ride and other times a distraction for dogs and wolves quite a lot larger than yourself.

Animal Well has become known for its multiple layers of completeness – anything past the first makes Symphony of the Night’s inverted castle look like Porky Pig’s Haunted Holiday. The game contains 64 (or more?) eggs (like easter egg, get it?) which are the currency required to reach the game’s second ending and some of these fuckers are devious. Anything past the second layer requires Getting Online And Getting Help (or, at least, there’s one solution that factually requires that.)

I’ll be honest – I watched FuryForged’s explainer videos for the later secrets of Animal Well, which I found too frustrating and minute to track. I have no interest in this kind of map combing, especially without the additional hint of at least highlighting where more secrets lie. Especially compared to Fish’s Fez, which this game owes so much debt it grants Gomez a cameo, this game went past my patience. The secrets started to be less about having insight into how the game works and more about willingness to poke and prod every corner or wall of the map. In my opinion, you should stick to the core conceit – find the four flames, each buried within an animal kingdom, and collect as many eggs as you can find. The game’s core puzzles really reward explorative play, with the items you find allowing for creative play without requiring the hyper-athleticism of a game like Super Metroid. There are sequences which encourage reactive thinking, sequential logic thinking, intuitive and deductive reasoning, simple navigation, and pretty successful platforming.

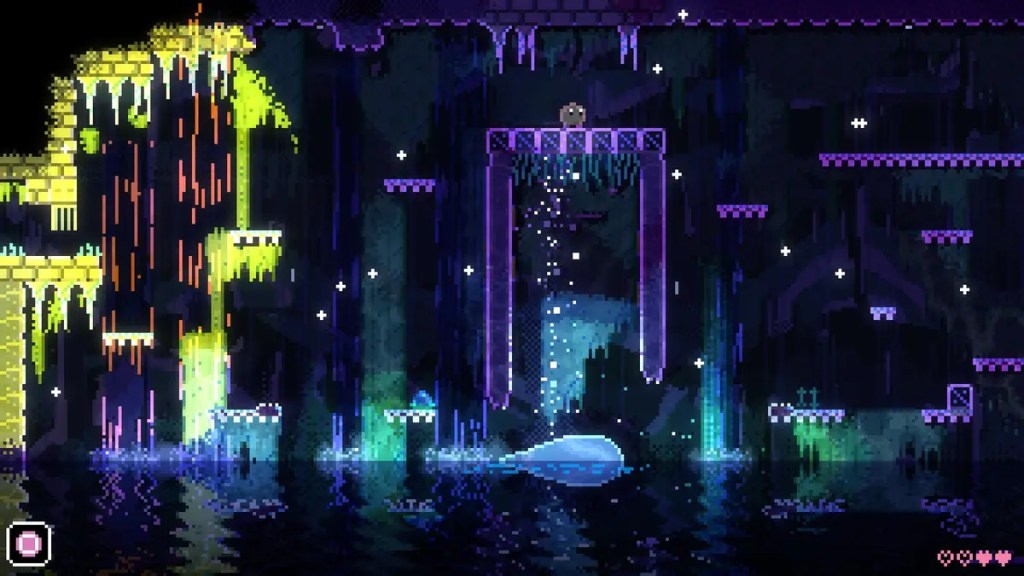

But for my money, Animal Well’s real triumph is the aesthetic. There are so many delightfully rendered pixel art animals in here. They make so many good noises and have such charming animations. They are shaded so damned well. Some are adorable and others are very threatening. And yet, despite the population of critters around, this game feels very lonely. The user interface stays out of your way and immerses you in this place’s darkness. Even compared to a game like Hollow Knight, there’s a sense that this well was something more. I admire the achievement of this game’s nonverbal narrative, its evocation of a world that once stood.

There’s also wonderful sound design in here. There’s a lot of rushing water and machinery, but the highlight is the number of creative animal sounds. Occasionally, something like the flapping of wings is produced more faithfully, but the vocalizations of animals are typically synth bloops very similar to Pokemon cries. However, unlike that game series structuring those cries as musical jingles, Animal Well tends toward short, evocative noises, like the gulp of a chameleon or the brief chitter as a squirrel shuffles away. A lonely cooing sounds off in the distance every so often, and finding its source is immensely satisfying.

Animal Well communicates everything it wants to say nonverbally. It occasionally will prompt you with a button to interact with something, but there are not text boxes explaining how to use your frisbee disc. That isn’t to say it’s entirely shy of language – there are pictograms, there’s musical notation, there’s gates associated with specific switches and keys. But unlike some puzzle games, Animal Well celebrates the notion of discovery as play by cutting out that form of communication. That it does it pretty intuitively, especially in those first two layers of play, is pretty impressive to me.

People smarter than me, like Balatro developer LocalThunk (who unsurprisingly will make an appearance later in this series), have declared Animal Well the Game of the Year. I say they are smarter than me partly because this game did not surpass the realm of solvable in their eyes and also because they have made some works I am awestruck by. I both wonder if I’ve had my eyebrows blown off by my one experience with Fez and just don’t care to get out the pen and paper again and wonder if I’m just not programmer-brained enough for this particular puzzle logic. But even not being able to go the full distance and embrace Animal Well as a masterpiece like they have, I still find the game to be quite memorable, affecting, and creative, in ways that make it an easy recommendation for my friends who love to stare at a game screen and wonder aloud if they’re stupid and know the answer is “probably.”