PAPRIKA

Dir. Satoshi Kon

2006

Satoshi Kon, whose life ended prematurely to pancreatic cancer at 46, attained a legendary stature directing four films and one television series. His most acclaimed film is Perfect Blue, his debut, a gnarly thriller about pop stardom and internet stalking, an outrageously prescient work, and it carries his trademark mastery of character motion and facial expression. When a character eerily moves too quickly, too lightly, it alerts the sense of wrongness quickly. He takes that skillset next to Millennium Actress, a dreamlike “biopic” of a fictional actress inspired by Setsuko Hara, using abstract fantasy to bring narrative propulsion and metatextual emotional depth. Recently reclaimed (after a much better translation to English) is his Christmas film Tokyo Godfathers, which celebrates found family with a flair of more cartoonish animation. And his television series, Paranoia Agent, was likely the introduction for many people my age who saw the show on Adult Swim, a mystery show about serial assaults by a young man with rollerblades and a bat. Its shockingly episodic structure and willingness to dramatically change tone from episode to episode create a memorable and challenging arc, and it represents Kon’s most dreamlike narrative thus far.

Kon’s career concluded with the film Paprika, in some ways a summation of every piece of Kon’s filmography thus far. Paprika is a dream therapist, using a science fiction technology called the DC Mini to participate in psychiatric clients’ dreams and record the encounter, working through repressed anxieties and symbols to identify traumas or needs. Paprika is also the alter ego of scientist Dr. Atsuko Chiba, one of the lead scientists of the DC Mini development team, who is using the device before it’s officially market tested and fully “safe” to use. When it appears that terrorists are using the DC Mini to invade people’s dreams and cause nightmares, delusions, and havoc, it becomes the DC Mini team’s responsibility to track down the people abusing the technology before the program is shut down permanently.

The film begins with an extended dream sequence with one of Paprika’s clients, Detective Toshimi Konakawa, who is experiencing debilitating panic attacks he believes may be related to the murder case he’s working. This dream contains elements recognizable to film fans – the film draws attention to Tarzan, but it also quotes The Greatest Show On Earth, and, most directly, From Russia With Love and Roman Holiday. When Paprika asks Konakawa about movies because of these references in his dream, he shuts down, even more than when discussing the murder – his trauma lies there, and he’ll need to be pulled through his own past to remember why he’s so stuck.

After Konakawa’s dream, the opening titles play. If you’ve never seen them, you can watch them now.

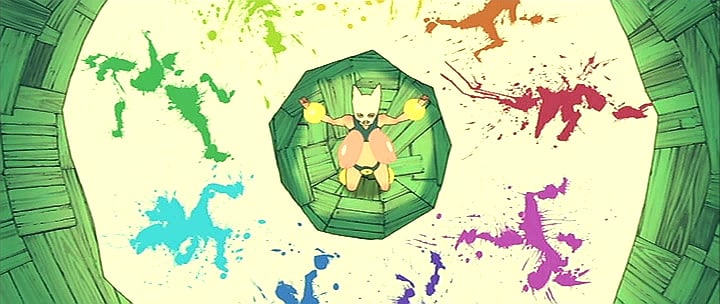

I have probably watched these opening titles a hundred times outside of the movie. For my money, this two minute sequence might be the single greatest work of cartooning in animation history. There are so many emotionally thoughtful ideas expressed with incredible economy. The way Paprika can transport and transform herself by way of images is a delightful power fantasy, the ecstasy of the digital pen giving her flight, teleportation, transmogrification. She is omnipotent but not entirely infallible – we see her caught off guard by rushing cars until she can stop them. I love the detail of Paprika putting the jacket back onto the sleeping office worker, whose desk has photos of the woman he loves at home – this all-powerful being is a healing spirit. But then she also doesn’t have time for boring, boorish men, and the image of her four reflected, increasingly disgusted reaction shots is only outmatched by her heading out to the street to coast away on the t-shirt of a rollerskater. I love the music by Susumu Hirasawa, music that is optimistic and futuristic, music that is a little off-putting but also catchy. And, lastly, I love that the transformation of Paprika back into Atsuko happens gradually across multiple cuts, communicating their different personalities before Atsuko speaks a single word.

All of these emotions are brought forward into the film, a film whose plot is hard to follow on a first viewing but whose emotions and vibes are immaculate. Elements of the shared dreaming were later made more familiar to American viewers by Inception, but it is otherwise a very different film – where Inception views dreams as a magic trick that works best as convincing its targets that the dream is really happening, a heist performed by experts looking to fool their client into believing the pitch, Paprika instead embraces the artifice in search of something grander. Postmodernism is often applied to works about dreams because their inherently abstract plotting bring to mind questions of identity and The Cogito, but Paprika goes a step further to embrace the communal and political aspect of postmodernism. If modernism is defined by the death of institutions, Paprika’s vision of postmodernism proposes that as the foundation for building the impossible.

Maybe the most iconic dream image in Paprika is the “dream parade,” the dream of a delusional patient where a parade of toys marches toward some unknown goal. The parade has its own terrifying electronic theme song. It also has a trademark nonsense poetry, one which starts somewhat incomprehensible but becomes a rhythmic series of absurdist social commentaries over the course of the film. The collection of toys represents different eras of traditionalism, from daruma and hina dolls to retrofuturistic robots and anatomical dummies. Eventually, cartoon characters and yokai join the mix – the clash of the Golden Age of Hollywood references and the electronic music of the postmodern title sequence returns again in the parade dream, and the battle between progress and conservation ends up being essential to understanding the film’s mystery.

This might make the film sound really intellectual and, well, boring – again, like the title, these ideas and emotions are generally presented simply as part of the action rather than in the endless dialogue of other philosophical films. These dreams are seen in thriller scenes of investigation and action, Atsuko exploring potential sites of danger, Paprika trying to identify potential dream invaders and fighting them off in fantastical chase sequences. The more impactful dialogue in the film is emotional – one wonderful scene between Konakawa and Paprika’s boss is them reminiscing over being in college, “when we used to talk about our futures.”

I’m going to wrap up this section because I’ve got a spoiler wall coming. Paprika is, since Tokyo Godfathers’ recent translation, often the bottom ranked of Kon’s films. I’d say this owes to two primary criticisms I’ve seen – the first is related to its portrayal of Dr. Kosaku Tokita, the primary inventor of the DC Mini and a very obese and childish character. While I have come to peace with Tokita’s character, there are undeniably jokes about his body that are fatphobic and meanspirited – Kon’s biggest flaw, across all his work, is how he handles unconventional bodies, generally marrying psychology and body in ways that can feel cruel. The second is general criticisms of the film’s plot and final act, which are confusing and can feel loose. In the spoiler section, I’ve identified a reading of the film that helps me understand both of these aspects, and I hope they help those of you who’ve seen the movie and are scratching your heads. But outside of the film’s relatively divisive final act, the very final scene of the film, which closes on Detective Konakawa, is one of the kindest and most wonderful endings to a film I’ve ever seen. I love Paprika. Rest in peace, Maestro.

SPOILERS FOR PAPRIKA

Let’s talk about the very climax of Paprika – we see the dream parade arrive in Tokyo. Paprika has been swallowed by the toy robot Tokita, and Detective Kanakawa has allied with the Radio Club bartenders, who have come to the real world through the spread of the dream. Kanakawa and the bartenders come across the great pit of despair.

Just before the Chairman emerges in his dark hole, Atsuko appears to Tokita to dream. She dreams of finally confessing her love for him, that the fact that he “swallows everything” is what makes him so much fun. Her coldness and cruelty at his childishness and obesity is what she thinks she’s “supposed” to feel about this genius savant. But in her mind, there is no one else. The dream then continues on, once the chairman appears, and Atsuko becomes the child who swallows everything. Through this dream, she vicariously experiences the thrill of eating it all up, the muck and the dreams, until she grows back to her adult, complete self. Finally completing this fantasy, when they wake up, Atsuko can finally be warm and loving toward Tokita, and they announce their marriage just before the credits roll.

It’s through this dream that Atsuko is able to finally make peace with herself and love Tokita. There is a subliminal thread of crosswired jealousy and romantic feeling throughout the DC Mini team. Tokita is at the center of the team, and his childishness allows him to focus on his creations, but he is also approval-seeking when it comes to Atsuko. Himuro is not envied by anyone, and we never hear his character’s true voice, but Osanai claims Himuro is jealous of Tokita as the head inventor – Himuro is also covetous of Osanai’s romantic affection, with Atsuko calling out Osanai “selling his body for the DC Mini” to him. Osanai himself is sexually fixated on Atsuko, but also is jealous career-wise of both Atsuko and Tokita, stating as much openly, even in his colleague persona. Chief Torotaro is in love with Paprika, and finds himself torn between his allegiance to Atsuko and her alter ego. But Atsuko herself only really thinks of Tokita, and her frustration, affection, admiration, and envy can only be sorted out by her experiencing a dream of his euphoric gluttony, much the same way Detective Kadokawa can only process his guilt by defeating the trauma in the dream.

This lingering thread also finally helps me close the loop on Tokita’s obesity. The romance between these characters never quite clicked for me, and the resolution of this nightmare image that goes unremarked upon really left me grasping for meaning and coming up short. Now, the understanding of this physical rejection as a barrier for Atsuko’s unspoken feelings about Tokita’s contradiction helped anchor his obesity as more than just a joke. Atsuko can’t see for herself the sort of therapeutic observation that Paprika can offer her clients – that she’s diverting a vulnerable, kinder feeling by affecting a societal cruelty against Tokita and herself. We’ve seen Konakawa resolve his arc just before the dream crashes into reality – I now understand the way the remainder of that dream concludes Atsuko’s.

“But what about the rest of it?”

After Atsuko saves the world, Konakawa receives Atsuko and Tokita’s wedding notice with a laugh. He’s already resolved. He leaves work and sets off for something to do. Posters for Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, Tokyo Godfathers, and Satoshi Kon’s unmade The Dreaming Machine decorate his walk. This scene, to me, is an impossible dream of imagining how we can reclaim our lives, the real power fantasy being the belief that we can, in fact, be anything, do anything, and find community. It imagines, after all the fantasy we’ve seen, that an equally powerful fantasy to saving the world is saving ourselves. Just before the film cuts to credits, Konakawa walks up to the box office and requests: “One adult, please.”