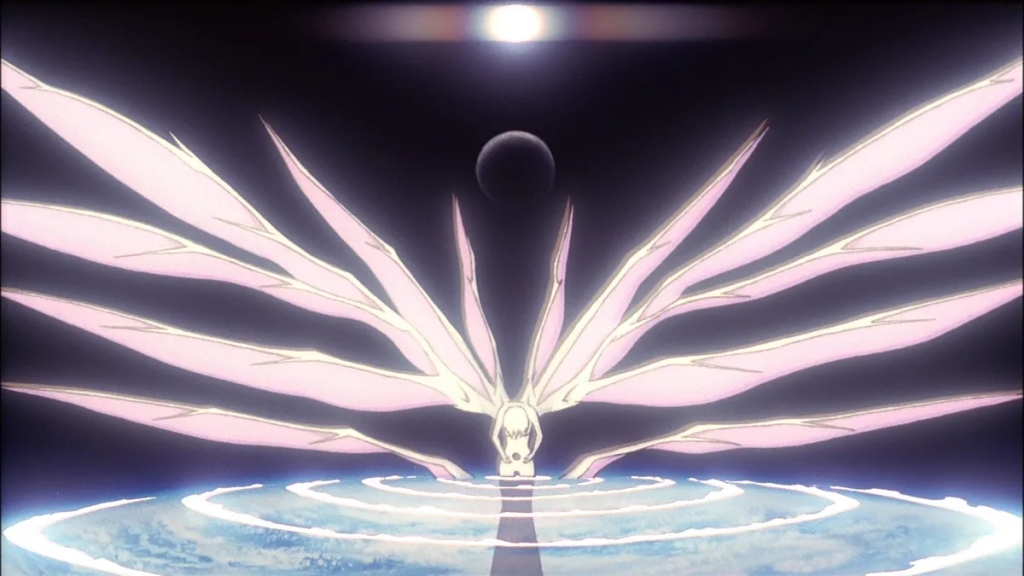

THE END OF EVANGELION

Dir. Hideaki Anno

1997

Neon Genesis Evangelion is a mecha anime about the end of the world. Teenagers face the horrors of the apocalypse, alien kaiju known as “Angels,” in their armored Evangelion suits, which are themselves more alien than machine and less alien than it seems at first. The adults in the room, an orgnaization named NERV, serve as their scientists, armorers, tacticians, therapists, parents, and jailers. The teenagers sometimes can put on a brave face, but their egos are being destroyed. Like teenagers in real life, a lot of their hyperfixations are on sexual desire, the difficulties of connecting with other people, and social performance. There’s a lot of lingering on teen sexuality in this show, including some leering at womens’ and girls’ bodies – for some people, this is a bridge too far, and the repulsion overwhelms whatever points the show is trying to make.

Evangelion’s fourth episode is titled (in English) “Hedgehog’s Dilemma.” This central idea, borrowed from Arthur Schopenhauer, is the central thesis of our primary POV character, Shinji Ikari. In essence, the dilemma draws a parallel between mankind and hedgehogs on a cold winter’s day. The hedgehogs wish to bundle for warmth to survive the harsh weather, but their quills causes pain – so it is with mankind and emotional intimacy. We want to be close, want to let our guard down, but rejection is too painful, and those who are too willing to accept that emotional intimacy will take on other peoples’ burdens. Shinji has elected to wall himself off from all emotional intimacy after the indifferent, abusive treatment of his father, Gendou – also the commander of NERV – and therefore constantly finds himself unable to seek comfort from loved ones despite taking on the immense psychological strain of piloting the EVA. This question of emotional intimacy defines Shinji’s arc throughout Neon Genesis Evangelion, and reflections of the Hedgehog’s Dilemma play out in the arcs of many of its characters.

The End of Evangelion exists as a theatrical sequel/alternate ending to the 26 episode anime Neon Genesis Evangelion. The original show ran out of money and its director, Hideaki Anno, ran out of mental health to guide the production. The myth goes that to fulfill the episode order with what little budget they had left and a network pissed off about the content in episode 24, they trekked forward with storyboard caliber sketches and cels drawn weeks prior for other episodes to create a last-minute ending, with The End of Evangelion representing “the true ending.” This ascribes the incredibly dense script of the final two episodes of the anime, filled with intense psychological and metaphysical dialogue about the nature of trauma and the relationships of every character in the show, to a hasty rewrite. That understanding also tends to ignore how this side of the show had grown over the back half of the series, and also that similar dialogue reappears in The End of Evangelion.

It’s unclear whether The End of Evangelion is an alternative ending to the final episodes of Neon Genesis Evangelion . Both endings feature the onset of the Human Instrumentality Project, a psychological melting pot that will return human consciousness to a single collective. In both endings, we see characters’ consciousnesses bleed into one another, sharing memories, being unable to hide away ugly thoughts, trying to win the final argument and reach consensus. One side argues Episode 25 and 26 depict in detail what’s happening internally, whereas End of Evangelion is more focused on the physical consequences of Human Instrumentality and the war to end all wars.

All these arguments about canonicity, about intent, get even more complicated when you factor in the Evangelion Rebuild project. Anno embarked on a remake of Neon Genesis Evangelion over the course of four films. But by the early scenes of the second film, Evangelion 2.0: You Can (Not) Advance, it became clear that the story was changing. Characters were suddenly arriving with altered names – their personalities didn’t line up, and not in a simple rewrite way – it eventually became clear these were new characters in old roles. By the third film, the plots had completely diverged, and the fourth film offers a new ending. Many Evangelion fans dislike the rebuilds and write them off entirely. In a literal sense, the rebuilds are the “true” ending in the sense that they conclude Anno’s emotional arc over thirty years of stewarding this series – he recently gave a statement that more Evangelion may be coming with his blessing, but he won’t be steering the ship.

In The End of Evangelion, whatever sympathy the show maintained for Shinji is dissolved. Shinji is putrid. Shinji is capricious. Shinji is motivated primarily by sex or hate. Shinji is emotionally catatonic because he was forced to kill the only person who’s shown him seemingly unconditional kindness since the show began – Shinji lashes out by objectifying every person in his life, sexually or as collateral damage. Because Shinji is the pilot of the EVA Unit 01, Shinji is given the keys to the Human Instrumentality Project. Will mankind maintain its borders? Or will it all come tumbling down?

Shinji fails to make a clear decision. We see the borders between people collapse in the musical “Komm, Susser Tod” sequence, a song that sounds like a Sgt. Pepper’s era Beatles track. The juxtaposition of gore, horror, and joyous sounding pop (with apocalyptic lyrics) – it’s the Feel Bad Movie of All Time. The End of Evangelion is full of great anime action, really strong character writing, and the show’s signature score by Shiro Sagisu (whose “Decisive Battle” is so good that he’s just kept using it in future works. But I’m fully willing to hear out any argument that The End of Evangelion is overrated within the broad Neon Genesis Evangelion project on the behalf of the powerful and sad “Komm, Susser Tod” climax.

While some anime fans criticize elements of Evangelion having been done before, in series like Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Mobile Suit Gundam and Space Runaway Ideon, the next sequence innovates in its combination of live action, insert documents, and animation. This sequence combines metacommentary about human existence by the show’s cast, footage of live-action cosplayers and fans attending the preview event for the film itself, and disturbing letters and drawings Anno received after the completion of the Neon Genesis Evangelion series – as it concludes, we see that Shinji has still not made up his mind. The limbo as he flip-flops between options becomes an unbelievable nightmare.

Together or separate?