DAYS OF HEAVEN

Dir. Terrence Malick

1978

After an opening credits set to archival photos of pre-WWI urban Americans, one of the first images we see is of glowing, hot fire. Bill (Richard Gere) works in a steel mill, and we see molten molding as our first major elemental power. This film luxuriates in vast expanses of the classic elements, on fields of wheat and riverbeds, on major storms and hair in whirling wind. Days of Heaven is most famous for its golden hour sunlight, fought for in protracted production to get twenty minutes of shooting done to get the rich colors captured in this film’s photography. But Days of Heaven never comes alive quite like it does in front of fire, which we see as the opportunity both to give life (such as at the final workers’ hoedown bonfire, sparks shooting off the central flame around the fiddler and the dancing) and to create hell.

I’m maybe lucky that my first Terrence Malick film was To The Wonder, the beginning of his autobiographical sequence I’ve seen people call “The Twirling Trilogy,” films extremely light on plot or consequence, heavy on reflective, poetic narration and beautiful people shot in beautiful lighting. After enjoying that introduction, I take any amount of conflict, plot, or Big Cinematic Beauty as its own reward. Knowing the hellfire that’s coming at the end certainly gives the preceding hour incomparable tension.

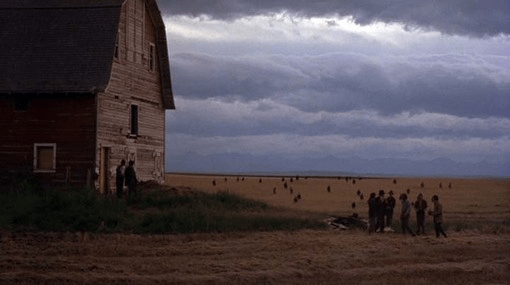

A good thirty minutes of Days of Heaven is mostly spent watching labor. After Bill gets in a fight and kills his steel mill boss, he takes his sister Linda (Linda Manz, who narrates the film) and his “sister” Abby (Brooke Adams, in an incredible double-header year where she also dominates Invasion of the Body Snatchers) to work on a wheat farm in the Texas panhandle and hide out from the law. The work of shucking wheat and collecting hay is shown in detail, repeatedly, broken mostly by moments where Linda is able to play with an unnamed friend. Annie referred to the pace as “a glacial 94 minutes” – I prefer the term “meditative,” but I’m a sicko for this stuff.

It helps that the golden hour photography makes the panhandle look like paradise. There are funny, storybook-like shots in the montage of the arrival to the farm. One shot of a train crossing a bridge in front of a bright blue sky immediately brought to mind Wes Anderson – a later scene at a river dock brought to mind Martin McDonagh. The definitive look of Malick’s modern films is shaped entirely by his collaboration with cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezski, and together they create deeply personal images which make me understand the appeal of sacred geometry. They are largely shot in immersive, close-up long takes, the camera’s sweep lively documentarian when people are in frame and methodical when shooting still images. His first two films, shot by (among others) Tak Fujimoto, Nestor Almendros, and Haskell Wexler, are no less gorgeous, but they present images in a more classical manner. The flashes of the future are here in shots of wildlife, from the rabbits and pheasants around the farm to the dread-inducing shots of locusts which threaten Texan Eden. And they are here in one riverbed conversation between Bill and Abby, an uncomfortable proposition that uses montage to show reconciliation.

The farmer (Sam Shepard) falls in love with Abby, and the drama progresses. In the latter part of the film, we see traditional dramatic acting in the triangle, and all three are so great at communicating their characters through body language and their facial expressions rather than through extended dialogue. But in the early part of their relationship, almost all interiority is only understood through Linda’s narration. Manz is somewhere between a real street urchin and a trained actor, having attended at least some classes but having run away for most of them. Because the film was largely shot in improvisation, Malick made a wonderful decision to let Manz narrate in post-production, apparently just a stream of consciousness improvised by Manz watching the movie herself. Her observations are so funny and so sincere – it truly creates the impression that they plucked this character out of a Faulkner novel and started rolling.

The great conflagration at the film’s climax feels like it could be where the film ends. It continues on another fifteen or twenty minutes, laying track for our “heroes’” fates, drawing some fairly clear delineation on what will or will not change. This decision feels mildly uncinematic, closer to the way a Great Novel ends, and filmmakers inspired by Malick (first thought in mind is Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist, but also Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s The Revenant or Jeff Nichols’ Take Shelter) often cut to credits right at that moment of Great Emotion. But that landing runway takes suit after his beautiful, surprising ending to Badlands, and predicts the iconic beach sequence that concludes The Tree of Life. Denouement is an essential part of Malick’s storytelling – it gives the story space to exist in context, to merely be where the curtain closes rather than where meaning dies.