I got spoiled in sequels this year.

Seriously, I’ve been waiting most of a decade for a follow-up to Animal Crossing New Leaf alone. If it had just been that, I’d already have felt that warm homecoming feeling. Instead, we got a full-blown “make games for Alex” season. Half of these I figured might come someday – a couple, I never expected to see exist at all.

Honestly? For a little while, toward the middle of the year, it was kind of exhausting. There’s such a thing as not being challenged enough, and at some point I started feeling like “I’ve done this already.” But the sad truth is, on top of all that, most of these weren’t revelations. Thankfully, only one of these is, like, going to get a dressing down.

A special shout-out to Final Fantasy VII Remake, which I could have put here instead of my previous Evangelion trilogy – but if I did, this blog would be even longer. Most of these writeups will be shorter than those. Keep an eye out for one more blog Friday. I’ll be starting and ending with my two favorites for the sake of getting the more up-and-down stuff out of the way.

Animal Crossing New Horizons

Animal Crossing likely deserves its own deep dive rather than a simple introduction here, but it also likely needs no introduction. Animal Crossing New Horizons is the shared experience I will never separate from 2020. So many of us burned through the game those first few months of quarantine – I know I’d assembled the village I planned to have years down the line by July, which led to me considerably slowing my time with the game. It is, as well established by now, the definitive COVID companion for those first few months for everyone who managed to get their hands on a Switch – for everyone else, there was Tiger King.

I played Animal Crossing New Leaf on and off after I flushed my original town – my next town, Guzzle, effectively closed down in 2015 when I graduated college, though I’ve occasionally checked in on my friends Stitches and Tia. New Horizons, due to the way I obsessively played during every free hour those first couple months, is already in that same holding pattern – I remember to check in every couple weeks for an hour or so, enjoying the organic groves and biomes I created, visiting with Marshal, Reneigh, and Tangy.

But Animal Crossing New Horizons is also a game that lives in me even when I’m not playing. When I remember the first time I walked through the museum’s fossil exhibit, which organically traces evolution in a way most real natural history museums should envy, I get very emotional. When I remember readying my outfits for my friend Ven’s fashion show, or watching my friend Gracie perform a seance (flickering the lights in her little Animal Crossing home for dramatic effect!) I think of some of the best, most earnest moments of play I had with a friend all year.

I don’t yet know how many games of the year there are – I’ve played at least nine. New Horizons is possibly/probably the best version of Animal Crossing, and Animal Crossing as a whole is better than any other game I’ve played this year. It’s unquestionably the 2020 release I played most, and it’s full of incredibly emotional details. It looks gorgeous, the music is great, I love the writing and laugh with the jokes, and it gives full power over the game’s traditional zen garden approach. And if “game of the year” means the game that represents a given year, it’s hard to deny Animal Crossing: New Horizons as the game for all of us this year.

Crusader Kings III

I don’t yet know how many games of the year there are – I’ve played at least nine. Crusader Kings III is one of the best games of 2020. It’s a deeply considered simulation of Europe, Asia and North Africa, where the player takes on the incredibly specific personal life of anyone from a baron to an empress. They will set on their plans with the goal of either mastering their domain or improving their station in life, siring heirs, warring, spying, feasting, and taxing their way through a story that encompasses a dynasty. Crusader Kings III improves on its 2012 predecessor by giving each leader more personality, improving on the simulation, and making the tutorials more accessible than ever.

But, I admit, I’m genuinely not able to pay enough attention to follow what’s happening in my own playthroughs of Crusader Kings III right now. I can make the personal decisions about who to spy on or hire as my vassal, but tracking wars or tax plans is right out. That won’t always be true, but during this pandemic? Yeah, I’m fried. The joy I’ve gotten out of Crusader Kings III has been watching my friends and favorite streamers play the game and get into increasingly absurd situations as they create pagan nations to challenge the Holy Roman Empire. Maybe when COVID ends I’ll have more focus in my free time.

The Jackbox Party Pack 7

Obviously, COVID became a great time for the Jackbox games, playable remotely with just an iPhone and a laptop, a great chance to kick back and crack jokes with friends. Party Pack 7 is just the most fun we’ve had yet with a Jackbox game – it’s such a wonderful platform to crack jokes on and reconnect through. I sort of wasn’t expecting the world of Party Pack 7 when it came out, but boy did it come through for me. Let’s play Champ’d Up or Talking Points sometime.

Spelunky 2

Spelunky is a 2D platformer where the levels are different every time you play – procedural generation assembles these levels to allow for a new experience every time. And when you die, that’s it, game over, start a new game. Using limited tools (starting with a bomb, whip, and some climbing rope,) the player navigates the game’s treacherous levels to try to finish the gauntlet. It may be my favorite game, period.

Writing about the original game back in 2012, I wrote, “Spelunky is a rushing dance, rewarding players who move quickly through the level with exceptional gamefeel and in-game rewards…In Spelunky, any encounter can be overcome with tight enough control of your explorer.” Emphasizing that dance was pitch-perfect encounter design, nailing what I think is exactly the right amount of difficulty from level to level. Playing Spelunky, I genuinely know that every death was out of my own carelessness.

Spelunky 2 promised more Spelunky, new discoveries, new foes, a new game to learn. Instead, Spelunky 2 feels designed only for Spelunky professionals. It feels tuned to make the first levels as difficult as the finale of the first game – I still haven’t seen past the jungle boss. I totally get why people who truly mastered the original game are getting so much out of Spelunky 2 – I hardly consider myself a neophyte, but I just can’t get there. And, uh, hearing this one song for 12 of the 17 hours I’ve played of the game certainly didn’t help – the original game had at least five different songs per world, and instead this feels like a pretty unfortunate misstep.

Golf on Mars

Hello, my old friend. How have you been? I like that new curl.

In my own opinion, my best writing is that which I’ve penned about Desert Golfing. Over the six years since the game released, it only changed the once – instead, I changed and it remained my constant. A sequel was something I never remotely considered could exist – it arrived one day unannounced, as the original did, and the collective of desert golfers began to Golf on Mars.

Golf on Mars plays much as the original did – using the touchscreen, the player pulls backward from the direction they want to aim the ball, drawing it like a bow and arrow, and releasing to launch the ball across the 2D dunes of red dirt. The ball moves a little differently through the atmosphere on Mars, and the clay offers less catch and less slide than sand when it hits ground. This game also adds the ability to put topspin or backspin on the ball by rotating a dial while aiming, meaning clever shots that utilize harsh hills or dynamic acceleration are more feasible.

Unlike Desert Golfing, every level is now 100% procedurally generated and unique to each player, and the game extends, per the app store description, into plausible infinity. This new approach has also led to the appearance of holes that are impossible to complete, a known feature that allows for really interesting or devious (but at least technically possible to complete!) holes, which has led to the game adding a skip button and 25 point limit on strokes for each hole. I can no longer share a hole with my friends and commiserate about how it is a real rude experience – on the other hand, every hole is now my own.

Unlike the static screens of Desert Golfing, your view can now scroll, as well. Overshooting can now send you catapulting past the next two or three holes entirely on the wrong decline, and being too timid can send you falling back toward where you started the last hole. This was, in my opinion, a phenomenal change that immediately makes a bad shot a source of comedy. It adds another layer of accountability to the formula – it gives Golf on Mars the systemic anecdotes of a game like Far Cry 2, of a grenade rolling down a hill.

At present, I haven’t emotionally connected to Golf on Mars the way I did Desert Golfing. Partly, it is the impossible holes, which happen a little too frequently for my taste. Partly, it is that I’ve already known Desert Golfing for so many years. But, really, it may just be that I haven’t written about it yet. I am still playing Golf on Mars – I am on hole 7019. I am still playing Desert Golfing – I am on hole 6154. I will be playing both for quite a while longer yet.

Deadly Premonition 2: A Blessing in Disguise

I was in genuine shock when a sequel to Deadly Premonition was announced, let alone announced to be releasing in six months. I’ve been the boatman for probably twenty souls in six separate playthroughs of the original game, a bastardized low-budget take on Twin Peaks that amps up the horror and the camp to sometimes unbearable degrees. Replaying the original once again in preparation for the new game, I was often struck by the game’s emotional vulnerability and sincerity – at least, its attempts at it, often marred by weak gender politics and a broad sensibility toward race and identity that lead to it falling into familiar storytelling traps.

Disappointing does not begin to address my response to Deadly Premonition 2’s Louisianan Le Carre, a town full of racist caricature, ableist depictions of dwarfism and developmental disability, and the worst treatment of a trans character I may have ever seen. It is a meanspirited and unlovable object by the time the game has unveiled its major twists. Upon receiving criticism for the game, the game’s director, SWERY, begged players to continue supporting the game and “hate him, not the characters,” a fundamentally embarrassing way to discuss the game’s loathsome content. There were many minute to minute charms that showed me I still love some of what Deadly Premonition has to offer, and yet I have not been this deeply repulsed by a game in years.

Yakuza: Like a Dragon

The Yakuza games have quickly escalated to become my very favorite kind of fictional world – one which is malleable and can flow wildly between high suspense, broad absurdist comedy, and soap opera melodrama. Playing a Yakuza game is equal parts exploring the strange and comedic world of its vision of Japan, exploring sociopolitical concerns by meeting citizens whose problems can only be solved by a combination of active listening and fantasy martial arts, and navigating a crime conspiracy of betrayal, petty greed, and collateral damage.

It’s sort of like if a Grand Theft Auto game had less emphasis on the darkness and depravity of the crime world and the inane superficiality of Americans and instead a focus on what support people need in order to overcome their sad lives. One sidequest involves buying time for an illegal immigrant to escape her loan sharks so she can finish applying for her work visa. In another, you teach a rock band that’s made up of posers how to really act tough before their first Tokyo concert. Hypothetically, you might help a burned dominatrix worried about paying the bills to keep her son in school get through to her exploitative boss, only to find out the boss is being blackmailed by yakuza and that’s the only reason he’s working her so hard.

The protagonists of these games do this by not judging people for their lifestyles, kinks, or past decisions – they adopt a progress-oriented stance asking, “what are you going to do about it now?” That same spirit applies to navigating different gangs in the main storyline, who make what they believe are impossible asks to assist you on your quest only for you to step up and do the damn thing. It can, however, get a little broad, with comedy occasionally overtaking the gravity of the story at hand – but that allows everything from the more serious sidequests at hand to a minigame where you desperately try to stay awake at a classic movie theater.

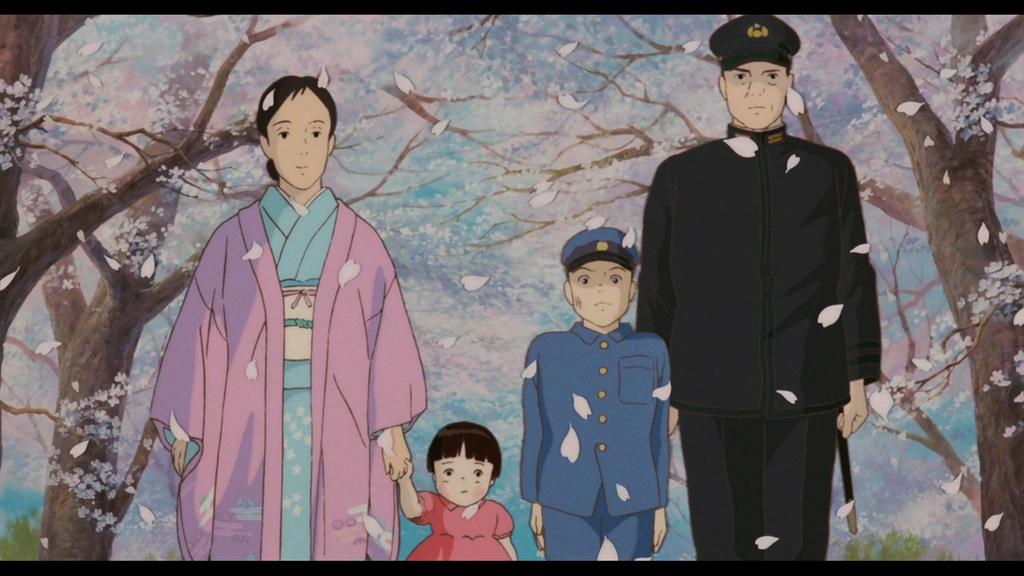

Previously, these games placed you in the shoes of “honorable yakuza” Kazuma Kiryu and his associates as an action beat-em-up – the original run of Yakuza 0 through Yakuza 6 covers roughly thirty years of his life, from the bubble economy of the 1980s to the ministry of Shinzo Abe. Kiryu, the “Dragon of Dojima,” is a bruiser with a heart of gold, and playing as him while he dropkicks some thug shaking down teenagers for money was a delightful experience – the action in these games is smooth and still deliberate, really rewarding the player for getting familiar with their abilities.

Yakuza: Like a Dragon begins a new storyline with a new protagonist, and introduces completely new gameplay alongside it. Ichiban Kasuga is probably twenty years younger than Kiryu and this game primarily takes place after Kiryu’s life of crime has ended – he’s a Dragon Quest junkie that agrees to serve a jail sentence for his father figure and yakuza patriarch, Masumi Arakawa, only to find the entire world has moved on while he was in prison. When he finally finds Arakawa again, Arakawa shoots him and his body is dumped in the red light district of Yokohama.

Unlike prior Yakuza games, the gameplay is now a turn-based RPG, complete with a job system and elemental attacks. They make light of this through Ichiban’s characterization – he lives his life the way a hero would in Dragon Quest, and therefore he sees every challenge that same way. The biggest change this makes to the story is that Ichiban can now have allies in his “party,” companions who can be present in every encounter and be just as involved in every step of Ichiban’s journey through Yokohama’s underworld. It’s both a great change for the story – which now can use the positivity of its protagonist to develop relationships over a much greater period of time as well as in sidequests – and for the gameplay.

Yakuza: Like a Dragon is a supremely fun RPG. Battles are fun whether they’re against street hooligans (complete with flavorful names like Pressured Cooker, Urban Ranger, and Officer of the Lawless) or the game’s rather challenging bosses. Choosing the right jobs for your party members (whether they’re going to serve as a construction worker, breakdancer, or pop idol) is just as important as choosing the right moves in every battle, considering spacing, your MP gauge, and which enemy you need to take out first to avoid everyone being wiped out at once.

All of that I expected before this game came out – the change to an RPG seemed well timed to accommodate this new start, and I trusted the designers to make the change for a reason. What I didn’t expect was for the story to feel so timely. Yakuza: Like a Dragon’s primary conflict is between three warring crime families as they try to resist external pressure. This primarily comes in the form of a dual-prong attack from the Omi Alliance (an oppositional yakuza conglomerate) and a populist conservative movement named Bleach Japan, with activists marching through slums to declare war on the “gray zones” where petty crimes like sex work or vagrancy are overlooked. That populist movement’s story feels informed and direct about the ways nationalist rhetoric and fascist minimization harm the marginalized – down to how cynically its leaders will use the rhetoric of being “hard on crime” to accumulate power. I won’t go into too many details of its twists and turns, but suffice it to say that Ichiban takes the side of the marginalized whenever he can, and it really is a heroic journey to watch play out.

I don’t yet know how many games of the year there are – I’ve played at least nine. I’m only about halfway through Yakuza: Like a Dragon. It’s a long, long game. I haven’t nearly finished it yet, so I can’t 100% declare its status, but so far I think it’s a miracle. Yakuza: Like A Dragon is the game of the year because it combines the best of Dragon Quest with smart changes relevant to the Yakuza franchise, adds in some social stats and social links borrowed from Persona, and still manages to beautifully capture the warmth, humor, suspense, and emotional depth of Yakuza’s best moments. To do so in a story that addresses rising conservative populism and police corruption…well, that’s the part I have to see the end of before I can really make a final determination.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/60433287/neon_genesis_evangelion_end_of_desktop_2616x2626_hd_wallpaper_1035766.0.jpg)

![Graffiti text from Umurangi Generation Macro's final level. The text reads:

"We Aren't The Smoke

We Aren't The Fire

We Are The Ashes."

"KOLUZUN IS NO ILLUZUN."

"have been topside. #stopcollateral)"

"I DON'T NEED PERMISSION TO NOT DIE."

"MOST COPS WERE 1ST WAVE VETS AND HAVE SEEN SOME SHIT THEY HAVE NEVER CLEARED."

"ALL PROTESTORS ARE CRIMINALS" = CHECKMARK. "ALL COPS ARE BASTARDS" = POLITICS.

"HIDE YOUR FACE."

"PICK A SIDE OR DIE."

"SORRY FOR NOT WANTING TO DIE."

"OBVIOUSLY ALL LIVES DON'T MATTER WHEN YOU KEEP KILLING US."

"IF WE ARE THE REAL BADGUYS THEN WHO ARE YOUR HEROES?"

"MY LIFE HAS VALUE."

"MONEY IS POWER

DRAIN THE MONEY

DRAIN THE [blank.]"](https://alexlovendahl.files.wordpress.com/2021/02/photo62043796.png?w=1024)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67551541/502515ee2c7e0520348.13650686_13S_Announce_2.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21999286/ogata_back_5a433e7e33.jpg)