This is kind of a sprawling piece, reacting to about a month’s worth of popular music and film. Unfortunately, to finish the piece, I’ll need to discuss the films Highest 2 Lowest (now available on VOD) and One Battle After Another (now in theaters) in-depth – if you’re cautious about spoilers, I recommend both films highly and to come back later.

Last month, my wife convinced me to attend Japanese pop artist Haru Nemuri’s concert at the Chop Shop in Chicago, one of few U.S. tour dates celebrating her new album, ekkolaptómenos. Nemuri’s music defies easy genre description, but “noise pop” with influence from riot grrl and nu-metal song structure would summarize it quickly. Her show was energizing, built on creating the crowd she wanted by encouraging a lot of audience participation and coming down from the stage to sing with us. Nemuri thanked us for being a safe audience for anarchism against fascism and bigotry, a place where the audience celebrated vulnerability, calls to free Palestine, with knowledge that touring in the U.S. under Trump is, to say the least, difficult.

We are past the phase of “interesting times” and find ourselves in violent times, with the United States government escalating violence domestically, at our borders, across the ocean in places like Gaza, even (cw: political violence) online. Like the violence of school shootings or civilian violence against public figures, these are largely not new campaigns, but they are escalating under current leadership. Not all art, or even good art, must respond to this moment – though if a film like Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another or an album like Geese’s Getting Killed can do so, it does feel like a lightning bolt, doesn’t it?

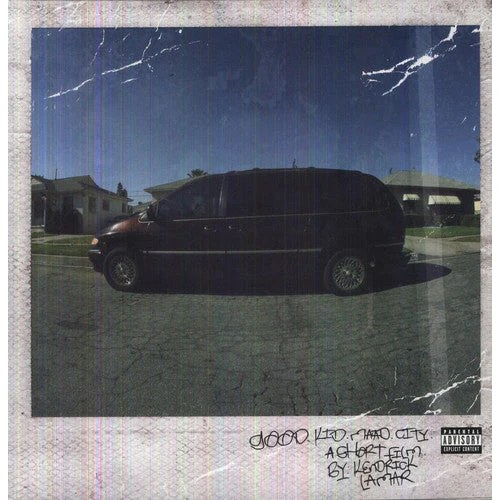

While Getting Killed lacks One Battle After Another’s outwardly political theming, its wigged-out bombast is very much a companion. Life feels surreal, apocalyptic, absurd, and Cameron Winter’s wild vocals and abstract, absurd lyrics feel apropos as the soundtrack to painful nonsense. The arrangements themselves are upbeat, textured rock songs, sort of in that New York art rock T. Rex/Television space (you can find drummer Max Bassin citing both bands here) that stand out against the more patio-friendly rock of bands like Cindy Lee and Wednesday (both of whom I like a lot!)

Getting Killed manages to catch the zeitgeist of a freaked out world by giving it an escapism that isn’t so clean that it’s a processed, predigested foodstuff. I found Cameron Winter by accident four days before its release – I drove home from Chicago from that Haru Nemuri concert listening to new releases, and Winter’s (also great, more acoustic) solo album Heavy Metal happened to be the twelfth or thirteenth album in the lineup. After ten or so disappointments in a row, Heavy Metal shocked the system by being something new, a casual, intimate songwriting with an astonishing vibrato and voice. Getting into Geese a few days later only to see “they have an album releasing tomorrow” was a funny surprise, and it’s been a rush to get into them alongside so many other people.

In contrast, Taylor Swift’s The Life of a Showgirl has failed to meet the moment and displays that she does not have the quality control she once had. I did try to listen to The Life of a Showgirl – I have to agree that it’s flat out bad, the low whisper-singing on the verses and the octave jumps into the choruses more often actively annoying than they are familiar vehicles for verses, even on supposed highlights “The Life of Ophelia” and “Opalite.” And, yeah, I think “Eldest Daughter,” “Actually Romantic,” “Wood,” and “CANCELLED!” are embarrassing songs for a woman my age to release. But I say “tried” to listen to this album because so often, it’s just flat out boring music, and any distraction from the dog asking to go out and pee to a Discord ping is easy to pursue to escape listening carefully. Unlike many Swift agnostics, I think she’s had quality control issues as far back as 1989 – I’d happily drop the back half of that album. This is the first time where I can’t find anything as good as “The Tortured Poet’s Department” or “I Can Do It With A Broken Heart” to highlight*. She only hit this new Drake-like insistence on releasing absolutely every scrap with Lover and the Taylor’s Version saga.

Someone asked for what reason Swift decided to write The Life of a Showgirl’s songs about fame, sex, high school, and mean girl shit when she frankly sounds so bored by it. There is, as made evident by her contemporary artists, more than enough to write songs about. I actually tend more toward Grace Spelman’s take, which is that writing about the peak of fame, exhaustion at touring, and being alienated from reality is a great subject for songs, but Swift’s approach lacks that personal touch. Instead, people are forced to project onto these vapid, self-annihilating songs as a derailment. Swift has been the subject of a lot of projection about her politics for years now, with her fairly limited political statements and her billionaire status. Suffice it to say I find it somewhat unproductive to care about what someone who doesn’t share their politics believes in private when they’re flying their private jet to go to the 7-11 or writing odes to reviling cancel culture.

The “bigger issue” I’ve seen proposed most consistently is that these songs lack any creative energy or mission – they feel like they were released to propagate the Taylor Swift machine. Swift continues to chase craven marketing stunts and alternate editions with exclusive tracks (the most recent count I saw put it at 32?) to up the price of participation in her album cycle from your monthly streaming subscription. Promotional materials for the album utilize AI generated imagery, and I complained enough on The Horizon Line about the way The Release Party of a Showgirl screwed up the theatrical rollout of new films. A recent Defector slam, Kelsey McKinney’s “No Good Art Comes From Greed,” quotes Dostoevesky to justify linking all of The Life of a Showgirl’s poor lyrics to her mercantile assembly line approach to releasing new music. McKinney declares “To create something, anything, good, takes time and desire,” that making art fast and for survival is going to lead to bad art.

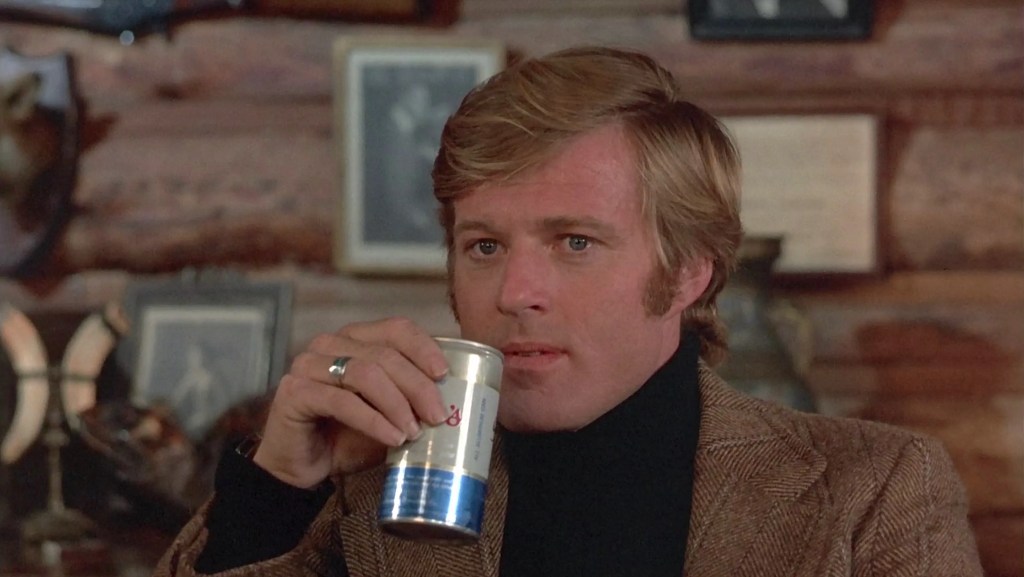

This same idea is espoused in Spike Lee’s newest joint Highest 2 Lowest by Denzel Washington’s protagonist David King. A remake of Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, Lee transposes the story to the record industry, David King replacing Toshiro Mifune’s shoe magnate with a mega-producer executive, Quincy Jones meets Jay-Z, mogul with an ear for hits. His wife (Ilfenesh Hadera) laments that King no longer seems enthusiastic about the music business, saying that when he listened to something good, he used to grin ear to ear while explaining why his was late to their dates. King seeks to buy back his record label Stackin’ Hits before it can be sold off to conglomerate ownership. He does this through a gambit of debt and promises,which are put in peril when he gets a ransom call from a kidnapper who claims to have his teenage (?) son. The film’s teaser trailer largely consists of a monologue King gives about the pressures that stack on star musicians before concluding on the sentence “All money ain’t good money.”

While many of the broad beats are the same as the Kurosawa film, Lee has altered the story, especially in the second half. If you haven’t, it’s worth seeing Highest 2 Lowest for yourself. The film is not perfect, certainly not as great as Kurosawa’s masterpiece, but it’s an exciting ride with an electric Denzel Washington performance, maybe my favorite performance of the year so far. In order to continue this piece, I need to discuss the film’s ending in depth – spoilers after the jump here until after the embed of “Trunks.”

I’m going to run down a synopsis of the back half, not because I assume you haven’t seen it if you’re reading this, but because I’ve interpreted the ending somewhat differently from other audience members. When King goes on a walk after the rescue of his chauffeur Paul’s (Jeffrey Wright) son (mistaken for King’s) and the loss of the ransom money, he puts on a playlist of songs by artists who’ve approached him for a record deal. He hears “Trunks” by an artist named Yung Felon (A$AP Rocky), and grooves smiling to it for about twenty seconds before remembering lyrics from the song Wright’s son overheard while captured, and believes he recognizes Felon as the kidnapper’s voice. He and Paul decide to take things into their own hands. King finds Yung Felon recording another song, “Both Eyes Closed,” and gives him advice on how to improve the track with some adlibs and stronger lyrics – after a back-and-forth about how it’s too late to give artistic feedback now, King and Paul apprehend Yung Felon, though Paul is blinded in one eye.

Yung Felon puts in a guilty plea deal, conditional on a conversation with King – this is a mirror to the end of High and Low, a last request as the kidnapper has received a death sentence after multiple murders. Before this conversation, we see a music video for “Trunks,” Yung Felon still in his orange jumpsuit, women twerking around him, and cuts to David King grinning and dancing joyfully. It cuts hard into the conversation – Felon proposes a record deal at Stackin’ Hits, saying that a collaboration between the now-valorized King and the man who took his ransom would be the biggest hit in the world. King informs him he’s no longer at Stackin’ Hits, looking to start something new – Felon insults him and asks why on earth he’d pursue “focusing on the music, when what’s more important than the money?” King rejects him, saying “All money ain’t good money.” He then goes to watch an audition by a young woman his son has recommended to him, a Best Original Song Nominee type ballad titled (for no clear fictional reason) “Highest 2 Lowest,” and King mugs his way through really listening to it before giving the monologue from the teaser.

Unlike some other viewers, I take this ending to be at least somewhat morally complicated. The fact remains that King relishes enjoying Yung Felon for nobody, and he is effectively in the spotlight for his family at the presentation of “Highest 2 Lowest.” For my reading, the part of him that is reveling in the power of music is lit on fire by “Trunks” and Yung Felon in a way that isn’t performative, isn’t aspiring to respectability or a better nature, and the performance of listening to “Highest 2 Lowest” (including being kind to the sort of performative, corny joke like “My father was a rolling stone – pun intended!” that nobody her age can honestly find funny, no?) is with lips pursed and head tilted, shouting “come on!,” never showing that beautiful Denzel smile until the song has hit its enormous conclusion and certainly never showing that same, dazzling grin.

Biased, I know, I’m biased – I’m bumping “Trunks” and “Both Eyes Closed” in the car, two of Rocky’s best tracks in years, and I would probably just as soon never hear “Highest 2 Lowest” again. But this is a film that, if not intentionally, can be read to admit that sometimes, great art comes from bad people with cheap motivations. King can never, realistically, take Felon’s proposal seriously – it would destroy his family, his relationships, and in reality, even 2-4 year prison terms can end a rapper’s career with an inability to tour or stay in the zeitgeist, let alone the twenty five Felon’s staring down. To make art with his family, who act like characters from a Lifetime original movie (and, arguably, have the actors to match,) he will have to settle for ballads Obama would forgo putting on his summer playlist to make room for charli xcx’s 365.

I understand the impulse to defend the production of art as a sacred, virtuous act, that the tainting of the grove with impure motives or methods will somehow lead to a decayed work. Even beyond the usual “is this TV show my friend” conflation of consumption as activism, artists and critics alike are broke, with fewer jobs, less revenue, fewer investments, and near-zero support from the state to produce work. The fact is that for most of us, there is no real financial motivation to create, and we do it purely for the love of the process itself. Even without getting into anticonsumerism and full political stances, the rejection of selling out often comes from a self-enforced acceptance that the sky is only the limit for those who start with the silver spoon, and the rest of us are really in it for the practice of making itself.

That desire also ends up being a double-edged sword. Returning to One Battle After Another, its focus on left-wing revolutionaries has led to many championing it as an invigorating call to action, a Truly Revolutionary Movie for our times. Backlash followed, not just from right wing commentariat sensationalizing hypothetical violence, but from farther-left radicals describing the film as both antirevolutionary and full blown COINTELPRO infiltration of leftist movements. I would describe it as none of the above. While I do think it has valuable thoughts about how we treat our allies and the people we aim to serve, as well as a willingness to believe in the titular battle after another, it’s less about What We Should Do and more what we choose to do in violent times. (The next paragraphs, through to the Twitter embed, contain light spoilers for the first two acts of One Battle After Another.)

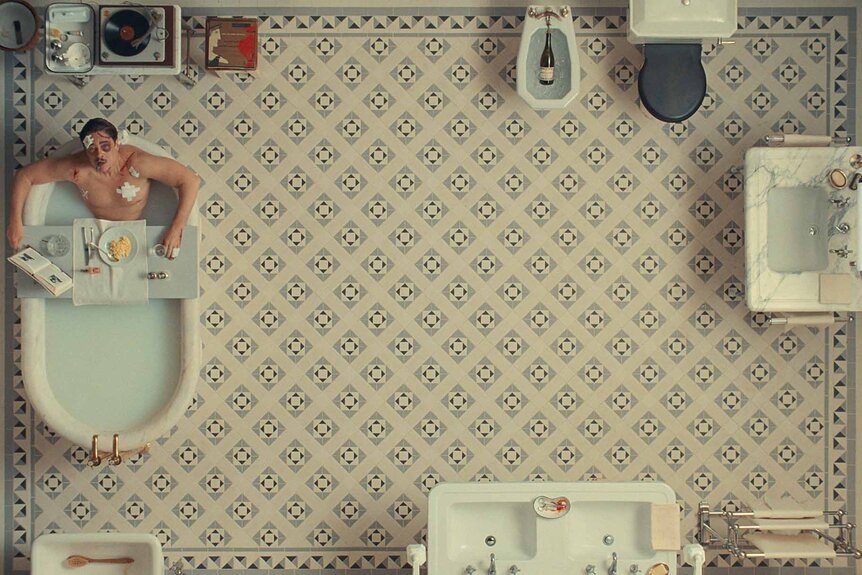

I’ll save more on the film for another time, as I don’t care to double the length of this piece, but there’s a continuity between One Battle After Another and Paul Thomas Anderson’s previous Thomas Pynchon adaptation Inherent Vice. Both films follow stoned post-radicals trying to navigate fascists and reunite with their loved ones. Unlike Inherent Vice, One Battle After Another’s Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio) was not just a hippie but an active revolutionary in his past life as Ghetto Pat, explosives expert for the French 75. But after the movement is compromised by Steven Lockjaw (Sean Penn,) he’s effectively in exile raising his daughter Willa (Chase Infiniti) while others have continued the work without him

Bob’s infirmed himself with copious substance use, social isolation, and a likely failure to get therapy after the departure of Willa’s mother, the revolutionary-turned-rat Perfidia Beverly Hills. When Lockjaw comes back, Bob’s utterly unprepared for the moment, though he at least trained Willa enough to get her to go along with one of his ex-75 compatriots. We see him link up with his daughter’s karate Sensei Sergio St. Carlos (Benicio Del Toro,) one of the year’s best characters. He’s the semi-mystical leader of his own subversive movement protecting illegal immigrants from immigration enforcement, and his movement stands in contrast to the password-keeping, scrambling, seemingly unhelpful remnants of the French 75. Even Bob has to rely on a personal relationship to get any assistance – the 75 doesn’t even seem to offer general advice over the phone.

This dynamic, along with the portrayal of Perfidia, has led to some of the better conversation I’ve had about a “political” film in some time, with productive conversations about “opsec” and providing community care, about the film’s out-of-time timeliness, about how this film depicts and looks at black women, and thankfully quite a bit about the filmmaking itself. I’ve managed to dodge a lot of the worst bad faith criticism of the film in my personal interactions – people are pretty thoughtful in their praise and frustration! I think the film is still my least favorite of Anderson’s films since Magnolia, but it’s a Real Movie, one that rewards analysis without becoming a monolith of praise, one that is enriching and is enriched by thoughtfulness.

But I have watched some of the hyperbole about the film from the roadside, both positive and negative. It’s this same puritanical desire to have every work that is Genuine and About Something to be itself Pure and All-Good, and either defend the film from any criticism or diminish its very praiseworthy elements. I have a harder time begrudging this for One Battle After Another, which I consider a great and also enriching film, as compared to some objects of hyperbole from the past couple years. Still, this hyperbole helps no one – it, in fact,

I hate to drag a specific film, but Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist got halfway there before derailing itself, and it merited this same sort of hyperbole and mission-like theater attendance. Sam Bodrojan’s “Don’t You Want Some Good Fucking Food?: On The Brutalist” actually dislikes the film more than I do, but is instructive for how it collapses in on itself, especially in the back half. I laugh reading her describe the way the film hides from looking at architecture despite its subject, focused more on the creative process and the compromises of its characters than the beauty of what they make. I cherish the way she deconstructs the film’s non-statement on Israel, summoned in the second act and film’s finale but ultimately not coherent. But The Brutalist is a film I like more for having read Bodrojan’s words on the subject, not less. It got me to engage with the film’s themes and details in a way that I received in the theater but hadn’t fully interpreted – that processing with someone else’s ideas is one of art’s magic tricks.

Someday, my great paean to criticism itself as essential to enriching art, my argument that “critic-proof cinema” is hermetic and eventually lifeless compared to that which you can stick your hands in and muck about with and Elevate To Greatness, will be laid out for you to read. In the meantime, I’d like to argue that timeliness and political correctness can be great assets in art, but are not the sole purpose of art. Art exists to speak to our times – art exists to make us dance – art exists because someone very good at something wanted to make money on it. Even Taylor Swift has successfully done the latter, in my book – “Anti-Hero” is pure commercial pop drivel, sexy babies and monsters on the hill, and it also has an unforgettable, glossy, delightful chorus. Political, ideological, and motivational purity are not at the heart of “what makes good art.” Find whatever drives you to make something – just make a point of making it well.

P.S. Shortly after hitting publish on this piece, I read Madison area writer and film programmer James Kreul’s piece on One Battle After Another – it’s exactly the kind of criticism I’m praising at the end of this piece, and I think you should read it!