THE PHOENICIAN SCHEME

Dir. Wes Anderson

2025

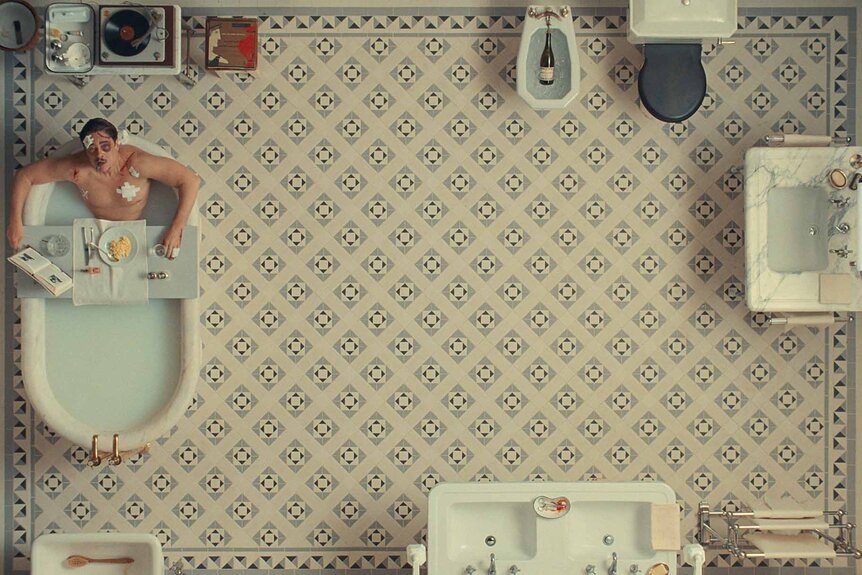

I have now said for years that I would happily go to a theater simply to see a montage of Wes Anderson costumes and production design ideas, and that the movies are good just happens to be a nice bonus. I advance the argument that Anderson should be considered among the most iconic and influential visual artists of the 21st century, alongside figures like Richter, Murakami, or (ugh) Koons. We see a version of his aesthetic, set in amber by The Royal Tenenbaums and Moonrise Kingdom, permeating public spaces and being cyclically imitated on social media. The infamous signifiers, the collections of kitsch arranged as storytelling, the orderly, clean lines throughout a space framed as a symmetrical image, and the emphasis on uniforms and dress tweed are more widely recognized than the visual iconography of any other live action filmmaker.

The Phoenician Scheme marks some noticeable changes in this aesthetic toolbox. Alexandre Desplat’s original music is largely variations on one moody, portentous theme, and the needle-drops trade Serge Gainsbourg and The Kinks for Stravinsky and Beethoven. Longtime cinematographer Robert Yeoman (who has shot every prior live action Wes feature, and many of the shorts too) takes this movie off and is replaced by Bruno Delbonnel, whose signatures often include strong green tones and more muted colors. These are never more feature-forward than in one of the film’s opening scenes, in which our lead Zsa Zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro) meets his soon-to-be-cloistered daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton) in the great foyer of their palazzo. It is an enormous, cold room, with nothing but a few paintings breaking up the slabs of gray-green, and more paintings sitting on the floor. Delbonnel gives the majority of The Phoenician Scheme this more muted palette, though later scenes are still sometimes flush with color.

Symmetry is broken at the start of The Phoenician Scheme rather than at the midpoint, when Zsa Zsa’s plane is blown open (with a blood splatter that made most of my audience immediately start cackling) and he’s forced to make a crash landing. Zsa Zsa is an unkillable cat and an unbeatable cad, the most ruthless and callous ultra-rich arms dealer in the world, and a combination of private and government interests will stop at nothing to see him either penniless, jailed, or dead. But even from the start of this film, he’s no longer capable of maintaining the rigid order that’s put him on top of this world, too physically beaten up and personally shaken down to keep the train on track. That’s reflected in his face, too, like in Bottle Rocket and so many Wes films before, cut up and bruised throughout the film.

So, what is The Phoenician Scheme? Loosely, it’s a corporate “public works” investment built on exploitation and swindling (the film is unafraid to confront Zsa Zsa’s intent to use slave labor) that will, in 150 years, provide a resource-rich base of operations for Korda’s military-industrial empire. Unfortunately, Zsa Zsa’s enemies have successfully created an unstable market for investment, and the film is spent watching Zsa Zsa, Liesl, and oddball assistant Bjorn (Michael Cera) travel from investor to investor and solicit the funds necessary to cover “The Gap.” It sets up a satisfying episodic structure for the film, though maybe none of the episodes delighted me so much as the first featuring Riz Ahmed, Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston. This episode in particular is so delightfully well-done, with so many perfectly timed jokes and such a strong commitment to not overstating any punchline, that I think it’s worth the price of admission on its own.

Anderson borrows a lot from the comedic language of his animated film Fantastic Mr. Fox here. There are deadpan repeated lines, a silent cartoon shrug repeated by multiple characters, and when action does arrive, the straight on close-ups and movement are so similar to the fight between Mr. Fox and The Rat that I immediately felt at home. Fans of the film are going to be repeating “Help yourself to a hand grenade./You’re very kind,” “Myself, I feel very safe,” and “Damnable! To hell!” in much the same way Fox encouraged “Take this bandit hat” and “Are you cussin’ with me?” to worm their way into your phrase book.

Like Fantastic Mr. Fox, I think that aesthetic sensibility supports the film’s emotional core. The relationship between Zsa Zsa and Liesl, and Zsa Zsa with his own peace, is a rich one, forcing them both to accept parts of themselves they’d rather push away without ever turning blame or judgment on Liesl for her reticence. Zsa Zsa’s been a poor father – hardly Wes Anderson’s first – but he’s also been a horrible person. Liesl, from the beginning, confronts Zsa Zsa with suspicion that he killed her mother, one of many women he’s reared children with (he has a horde of ten or so misbehaving, unwanted sons, some wanted and some not, a throng raised down the street except on Saturdays) and he furiously denies it. Over time, he comes to grips with his role in her demise, while also facing near-death visions of an afterlife where his soul is not measuring up to heavenly standards. Many have made comparisons to Powell & Pressburger – I don’t disagree.

There’s also the question of the film’s political angle. While many describe Wes Anderson movies as “not really about anything” except for being beautiful or funny, his last five or so films are quite political. The Phoenician Scheme is less about “politics” rather than the realpolitik of hypercapitalism, and Anderson uses securing funding as his mechanism for exploring that. I’m sure it’s quite relatable to Anderson, whose films manage to be made with incredibly star-studded casts for fairly low budgets and filmed where he can catch tax breaks for the arts. He portrays this world as being built almost entirely on interpersonal values and the merit of one’s word – Zsa Zsa doesn’t ever successfully find a contribution to The Gap by sweetening the pot or finding a mutually beneficial deal, he does so through emotional, interpersonal appeals. It’s unclear whether or not the near-death experiences and confrontations of his soul have changed his tactics, his execution, or his follow-through, or if the money’s always been this fake.

This review is built on examining the film in this more serious way because, well, I want to push back on the idea that this is a Minor Wes Anderson film, or that Wes Anderson films are all fluff. It’s a supremely funny film, and most people will come out of it laughing about Michael Cera’s incredibly funny character performance as Bjorn the assistant/insect tutor, Ivy League sweats, or the deadpan of Del Toro and Threapleton’s mile-a-minute dialogue. From the opening credits set to Apotheosis from Stravinsky’s Apollo, It’s a real treat of a movie, and I don’t mean to diminish that. I just have spent the last three days thinking about it on more than just those terms, and look forward to doing so for quite some time – and I wanted to put a rave out into the world before it leaves theaters.