Watching Shelley Duvall’s 70s work, I find myself confronted by an unvarnished truth. In a movie like 3 Women, Duvall plays both the underlying frustration and the surface level facade of genial perfection with equal honesty. Neither should qualify as a spoiler – compare first this clip of Millie’s genial side, and then this one of a milder snap. There is a truth to what many consider a mask – it is a presentation of the idealized self, sure, but our ideals can also be part of us. Duvall performs a psychological complexity that many misunderstand. The ugly things we say are not truer than the kind ones just because our politeness holds us from saying them. The things we say to wound based out of rash impulse are not inherently “more honest” than the ones we use to glide above anger and social mismatch. I think Millie is being honest in both clips, and it’s given to us as the audience to read her reaction to Mildred (Sissy Spacek) for what she’s feeling.

Duvall’s Millie, like many of her characters, isn’t psychologically complex because she’s an obvious intellectual. If anything, Duvall’s characters are often defined by a sort of cluelessness, either by living simple lives or ignoring red flags. Part of it is just that she’s damned funny. She was funny in Nashville as an outrageous boy-crazy It Girl flown in from L.A. Funny as the disreputable (and insightful) Countess Gemini in Jane Campion’s otherwise po-faced The Portrait of a Lady. Funny as the Astrodome tour guide who hooks up with Bud Cort’s Brewster McCloud in her first on-screen role. But she was also funny in real life, in profiles like the 2021 THR piece Searching for Shelley Duvall, a profile in which she dispels some of the more despairing images of her struggles with mental health and trauma. (I’m saving thoughts on The Shining for its own piece, but Duvall is the real masterful performance in the film. Suffice it to say that I believe her repeated account that Kubrick was warm and friendly and that the work of making The Shining was emotionally exhausting for almost everyone involved.)

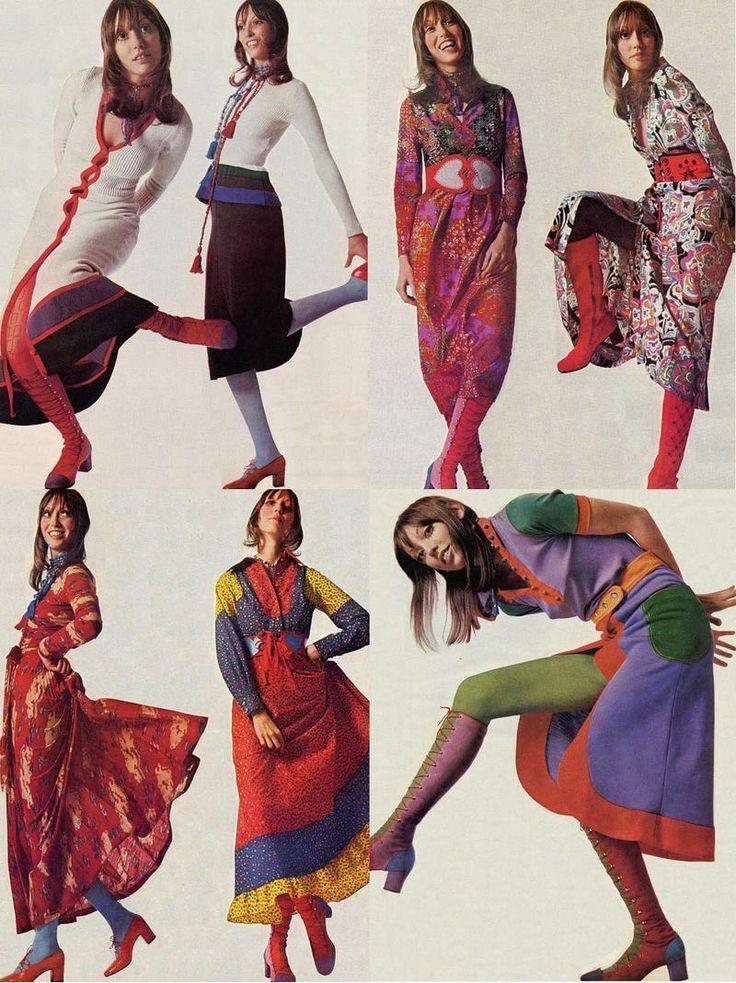

Maybe more than anything, the throughline of Shelley Duvall’s canon confronts our understanding of who gets to be iconic. Part of it is the colorful aesthetic that defined her personal fashion – it’s no surprise looking at her combinations of color and pattern that she’d become invested in children’s programming and fairy tales. That aesthetic means a lot to me. Looking at some of Duvall’s choices of clothing invokes a sense of comradery. It’d be too simple to call it “camp,” but there are choices in her makeup and her wardrobe that expand my own sense of queer euphoric fashion.

It’s also her choice in roles, bringing that complex version of emotional vulnerability to characters of all classes, levels of status, and ranging from victims of abuse to literal cartoon characters. I haven’t seen a couple of the landmark Duvall films. Many of my friends mourning Duvall have posted scenes from Robert Altman’s Popeye, a reclaimed gonzo blockbuster adapting the classic cartoon – it’s hard to imagine a more obvious Olive Oil. Two of her 70s Altman collaborations, Thieves Like Us and Buffalo Bill and the Indians, remain on my queue. I’ve heard a lot of love for her work in the original live-action Frankenweenie, and I’ve seen none of her children’s programming at an age I’m old enough to remember. I’m thankful for a little more Shelley Duvall on my horizon. I’m glad she passed celebrated by her friends and community for all the beauty she brought into the world.