STREET FIGHTER III: THIRD STRIKE

Capcom

1999

PC, Xbox, PS4, Switch (part of Street Fighter 30th Anniversary Collection)

If you’ve never seen it before, watch the embedded clip.

Street Fighter III: Third Strike is partly notable for its parry system. By flipping the control stick toward your opponent at the right moment, you can deflect all damage from an attack. This is a little risky, because hitting the opposite direction will block the attack whether you’re too early or not, more safely allowing you to defend 75% of the damage. Parrying also allows you to much more quickly launch your own counterattack, preventing your opponent from having time to guard themselves. In the above clip, Daigo Umehara as Ken at the very bottom of his health bar parries every hit in Chun-Li’s fifteen hit super combo, with each parry offsetting the timing for the next hit, before launching his own surprise super and winning the fight against Justin Wong. Daigo went on to win the tournament (a Street Fighter fan corrected this failed memory – he made Grand Finals, but lost to Kenji Obata!) and become known as the greatest fighting player in the world for the next decade.

One of the complaints that comes up around learning some Street Fighter games is that they’re too simple, your responses to your opponent’s strategy too programmable, and that leads to a game that can feel kind of stale. This is part of why it’s become a popular learner’s game – one of the best intro to fighting games primers I’ve read centers first on the most basic match, Ryu vs Ryu, and argues that this mirror match basically makes up all variations on the game’s strategy questions. A lot of Street Fighter’s core design is a triangle of decisions – you can guard to try to mitigate damage, you can attack and risk getting hit, or you can move and try to improve your position. Within each miniature situation, variations on this triangle will play out – attacking high, low, or from the air – attacking with projectiles, punches, or grappling through guards – blocking high, low, or jumping to dodge. Those nested triangles break apart what otherwise might play out as a rock-paper-scissors game, like the Mushi-King arcade cabinets in Japan.

The parry breaks apart these triangles by offering a new gamble. Because you can take that risk to avoid all damage and counter more quickly, all courses of action become a little more dangerous, leading to a series of choices that open up that triangle (into more than just a square!) Where your opponent across the screen might have felt safe throwing fireball after fireball because the only way for you to approach him would be to safely jump over each one, opening you up to a big uppercut, now you can walk forward, parrying each projectile, advancing while maintaining your own momentum – provided your skill at parrying is high enough to not open yourself up to punishment.

I knew I wanted to get a fighting game in here, mostly because I love them but rarely play them these days. When I was in college, my roommate Jake and I could sit for hours getting one more match in of Super Street Fighter IV, Marvel vs. Capcom 3, or Third Strike, learning more against one another than against any other opponent. Jake would drill combos, watch videos, read strategies, learn advanced techniques in the lab. I rested on my fundamentals, learned my handful of characters, got as in-tune with their capabilities as possible.

Coming back to Third Strike a decade later, the only two characters I even remotely remember are Ryu (who I play in every Street Fighter game, including the quite excellent Street Fighter 6) and Elena. Elena represents what I love most about Third Strike – she’s a lanky capoeira fighter whose moves flow comfortably into one another without becoming long dial-a-combos I had to master in hours of practice. While she’s unpredictable and difficult to manage for new players, she’s actually one of the weaker characters in Third Strike – her moves require very perfect timing or else trap the player in relatively lengthy animations that are easy to defend against. But her unique fighting style, bubbly personality, and shock white hair make her a memorable part of the Third Strike ensemble.

Street Fighter III famously brings back almost none of the iconic Street Fighter II cast – Third Strike’s nineteen character cast makes a concession by bringing back Chun-Li alongside Ryu, Ken and Akuma. Only a few members of that cast have come back in future entries and only in re-releases or DLC expansions, meaning most of them are best learned in Third Strike itself. The new cast is a little less superhero-comics oriented than Street Fighter II’s – whether that comes in the form of cool, hip designs like Sean or Yang or the horrific oddity of characters like Oro or Necro.

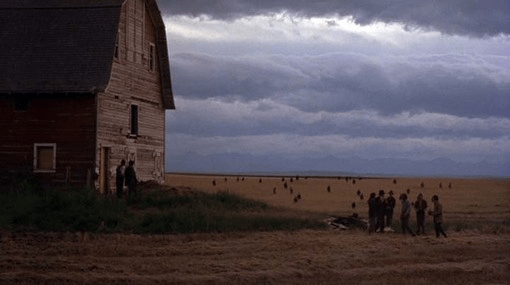

All this is realized in a pixel art aesthetic that remains unmatched. The animation on character movement is so fluid and expressive without requiring the outsized toon faces of something like Metal Slug. The backgrounds include empty streets, rainy rooftops, and grimy subway stations, giving the game a real backstreets, underground spirit. The soundtrack combines breakbeat and instrumental hip-hop better than almost any game since, a dealer’s choice of cool sonics that also lay a foundation for any number of melodic approaches on top, whether that’s needed to capture a runaway shinobi’s melancholy or to just launch into a perfect jungle breakdown. I couldn’t possibly tell you the story of Third Strike – Street Fighter lore is immensely detailed and requires playing hundreds of hours of mediocre single-player gameplay when it doesn’t also require reading addendum comics. But I can tell you this world feels a little dangerous, a little like the few heroes of its past that still walk its alleys get assailed by private detectives and snot-nosed kids with a mean right hook.

Most of my experience with fighting games these days is watching tournament and stream highlights. I’m in the iconic fighting game Hard Drive dead zone, and I have neither the free time nor the drive to get better. Tournament highlights from Third Strike are always enjoyable because the game’s unique cast is still complex enough to reward playing the vast majority of its characters and the game’s pace is not so fast that the combos are unreadable. The animation clarity is smart, too. The hits that deal the most damage look like the hits that do the most damage. The supers zoom in and let you know when something serious is about to happen without interrupting with a long canned animation. It’s just so many small, intelligent decisions like these being made to make a game that’s lasted twenty five years.

Daigo Umehara still plays regularly, but he’s fallen to the wayside over the past twenty years. Justin Wong actually has maintained a better overall win percentage across more games, his fundamentals allowing him to transfer his skills to games like King of Fighters, Marvel vs. Capcom, and Mortal Kombat, but Wong still finds himself streaming Third Strike regularly. It still gives me pleasure every time I see someone square up against Justin Wong’s iconic white Chun Li hoping to reclaim the greatest moment in fighting game history.