Higurashi: When They Cry

Ryukishi 07 + 07th Expansion

2008-2022 (it’s a long story)

PC

The memories I have of playing Higurashi: When They Cry involve the nighttime dog walks after a session just as much as the experience sitting in front of my computer. The idea of the “mystery game” has existed almost as long as games themselves. Ken and Roberta Williams created the murder mystery adventure game Mystery House in 1980, the start of their storied careers. But many of those mysteries have fatal flaws. Sometimes, they are too easy to deduce, with plot beats that land as thudding “WE KNOW ALREADY” moments. Other times, they’re impossible to deduce, either because the reality is far too implausible or because the game actively lies to create tension (maybe never more infamously disappointing than David Cage’s Heavy Rain.)

Higurashi: When They Cry is a mystery that trades on familiarity. A “sound novel,” or a visual novel with an emphasis on atmosphere in its storytelling, perhaps its most famous signature sound is the cry of the titular “higurashi,” summer cicadas. It’s a sound I grew up hearing in my midwestern suburb, not as lushly textured as the sound of Hinamizawa’s forests and fauna. I grew up with similar anime, too – a protagonist-attituded teenage boy, Keiichi Maebara, moves to a new town and meets a high-energy cast of teenage girls. After getting friendly with them and beginning to develop relationships, he participates in the town’s summer Watanagashi festival, a local tradition with carnival games and sweet rituals. After this festival, however, bodies turn up – an unfortunate recent event is the annual deaths on the night of the festival. Keiichi has been friendly with these victims, too – and, unfortunately, it may have associated him with the grudge that took their lives. Now, Keiichi must do his best to navigate a network of suspicion, often suspecting even the friends who took him in of the violence he fears may come his way next.

I say “often” because Higurashi’s storytelling structure is fairly unconventional. The game is divided into eight “chapters,” each separate executables, and a newly released (June 2022) epilogue. Each of these chapters is not sequential with one another. Rather, they offer alternate scenarios – the first four scenarios, the “Question” Arcs, portray alternate versions of the Watanagashi Festival and the violence that ensues. Different characters may appear, different decisions get made, and, ultimately, different unfortunate misunderstandings set friend against friend. The latter four scenarios are the “Answer” Arcs, and they offer different perspectives on the events of the Question Arcs – and, as a result, often far more information about the ultimate cause of this violent ritual.

Each chapter plays out with a fairly regular structure – the first half plays out as a slice of life anime, really dedicated to fleshing out the characters and building affection for their friendships. I can’t stress enough that if you don’t have much tolerance for 2000s anime comedy, this is probably gonna be a tough sit for you. It’s worth noting that sexuality is never explicit in Higurashi (valuable in a series about literal teenagers!) but it does lean into tropes about Keiichi sexualizing his classmates, “RANDOM!!!” humor, and meta gags. In high school, this was the stuff I ate up with an appetite – shows like Lucky Star, Azumanga Daioh, and The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya were my favorites. That last one owes a massive debt to Higurashi – I doubt it would have been received the same way without a loyal Higurashi fanbase, if it were written the same way at all without its predecessor.

After the laughter, dread sets in – the Watanagashi Festival has arrived. After the first chapter, you’ve come to learn what this will mean. And you know that shortly after this last gasp of friendship, the despair comes soon to follow. The thriller sequences of Higurashi are among the more terrifying horror novels I’ve read in a long time. The violence isn’t necessarily excessive, thankfully. The quality of the writing allows for genuine dread to instill, and the sound novel aspect allows it to really punctuate horrific moments.

Every Arc is, in my opinion, quite satisfying. The first is very much an introduction to the world, and it plays out in ways that might feel somewhat predictable to fans of the genre. But its primary suspect for Keiichi, a disturbed version of the girl next door, Rena Ryuuga, has a handful of moments that are chilling. And, even better, there’s elements you can’t explain right away. For one thing, it wouldn’t seem like she’s acting alone, but no explanation of her behavior can account for how she’d have accomplices. For another, one cause of death – seemingly self-inflicted lacerations, which merit more detail but I don’t want to spoil – can’t clearly align with anything you’ve seen. You’re left piecing together what you can.

Those nightly reflections on my Higurashi readings are so memorable precisely because I really was able to piece together a good amount of information I hadn’t previously been told without ever giving the whole mystery away. I’d walk around, asking myself what I’d learned that night, trying to piece together the ultimate mystery. I’d think about these characters throughout my day, remembering my favorite moments, both happy and sad, scary and funny. I really grew to love them, and so solving the layered, quite complex mystery was my full hobby for almost a month as I binged the game.

I’ve often said that the runtime approach to games is totally skewed. Sure, I played the PS3 game Journey for three hours. But when I thought about it for a decade afterward, listened to the soundtrack repeatedly, and acknowledge it altered the way I thought about the transcendental – did I only get “three hours of value” out of the game? Higurashi, even just in terms of screentime, is a long game – I made liberal use of the game’s fast-forward button to get all the text on screen at once, and Steam says it still took me 50 hours to complete. If you use the popular 07th Mod to add voice acting and actually listen to all of it, you’d probably hit 120 hours of game time easily.

It took me three weeks to read, and it honestly wasn’t long enough. Higurashi is easily one of my favorite games ever, and has made me rethink my relationship to games. The novel originally released over five years, the first chapter releasing in 2002 and the eighth in 2006, and then released in the US between 2008 and 2010. It’s expanded into anime, live action films, anime sequels, spinoff games, and, of course, the maybe even more popular spiritual successor, Umineko: When They Cry. I’m giving myself time to live with Higurashi as the end of the story for now – but it’s partly that I know there’s more to discover, more time to live in the world of its writer, Ryukishi07. Compared to certain other recent mystery games (*cough*Immortality*cough) I can only just barely wait to fall back into this world.

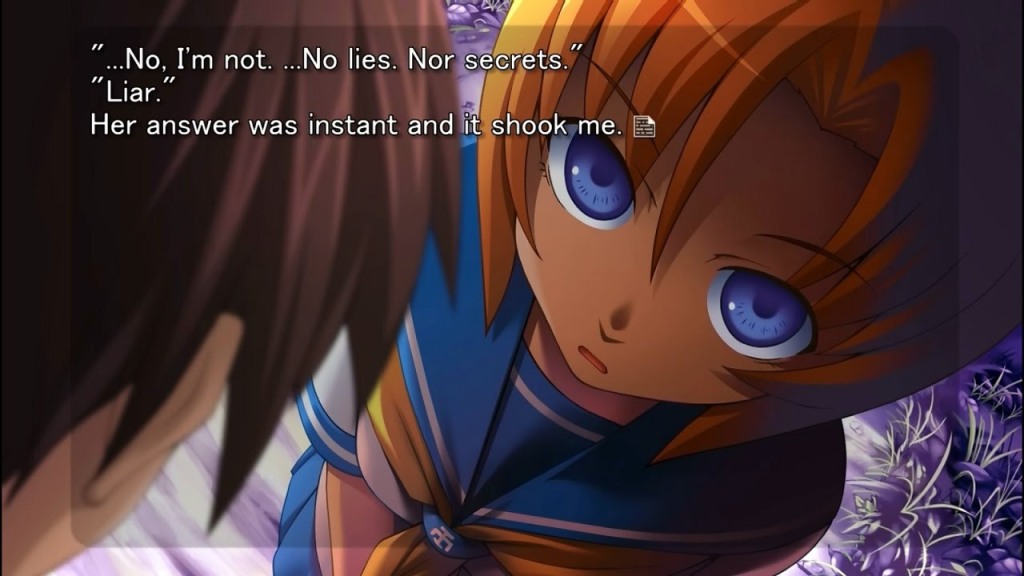

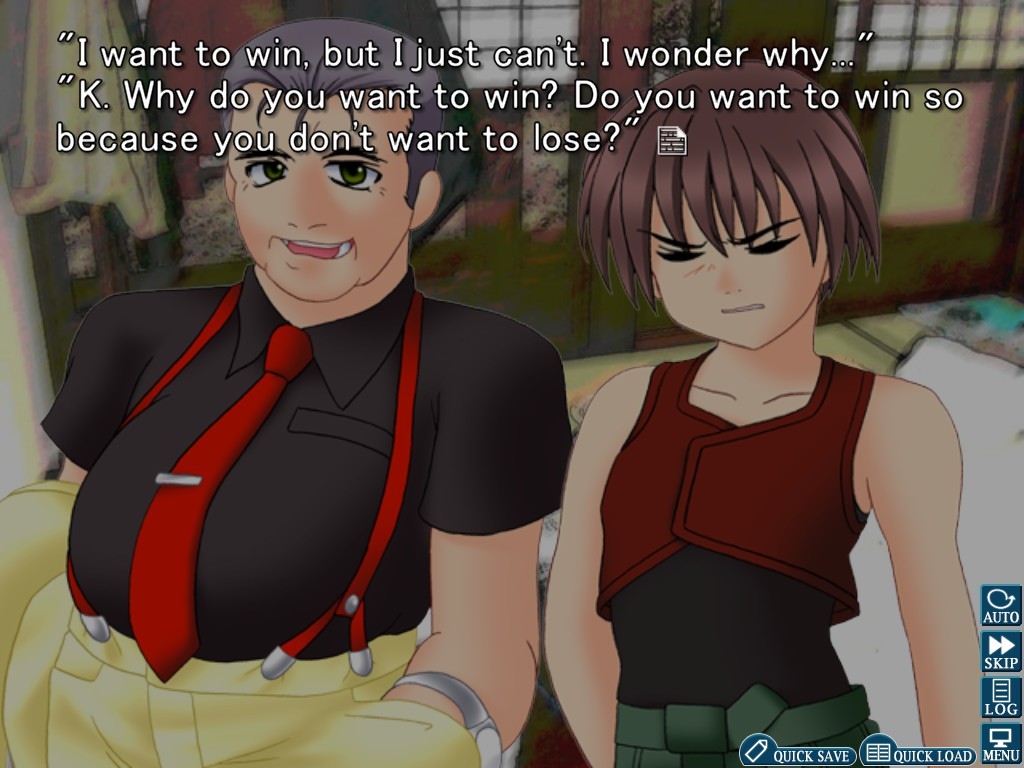

Additional notes – the Type07th Expansion mod, and the “original” art. The Steam version of Higurashi, released between 2015 and 2016, allows you to switch between the art you’ll see on the new Steam page and the original art, the conversation you can see between Keiichi and a local cop. I am not going to argue for anyone to play with the original art unless they really want to – it definitely has a lot of personality, but, uh, it’s obviously a lot harder to take seriously. I did not install the popular Type07th Expansion mod, which adds voice acting and the art from the PS2 release- you’ll see it in the image above this paragraph. Most diehards swear by the Type07th Expansion mod. I didn’t install it. I personally preferred to play without voice acting, which allowed more ambiguity in a lot of the line readings, and the Steam remaster art is totally acceptable IMO. But I figured I’d make you aware of it, because many other diehard fans would cuss me out for not making you aware that you could play this game with what, from what I’ve seen on YouTube, is excellent voice acting!