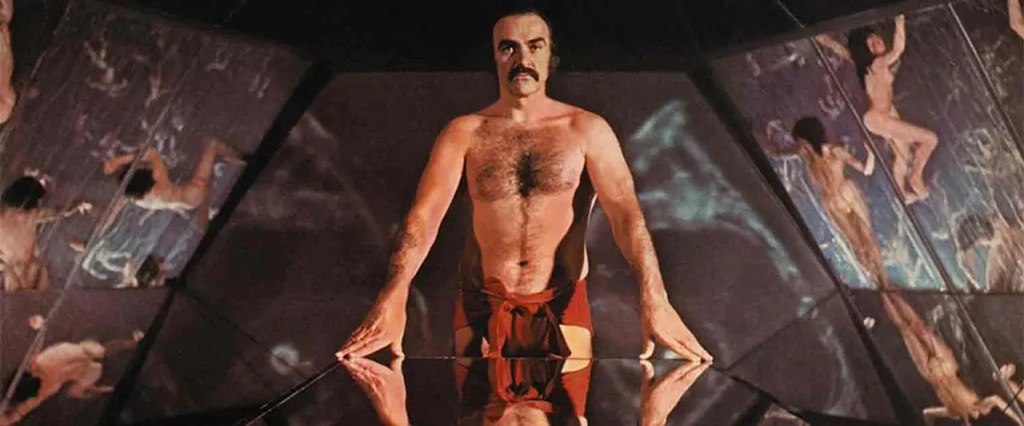

ZARDOZ

Dir. Jon Boorman

1974

If you’d like to know why I think Zardoz is, quietly, one of the best, most intellectually provocative science fiction films of all time before watching, go ahead and keep reading. (I also just bought a brand new book on Zardoz, Anthony Galluzzo’s Against the Vortex: Zardoz and Degrowth Utopias in the Seventies and Today, so I may be writing about Zardoz again soon.)

Every time I’m reunited with Zed, Consuela, May and Friend, I find myself thinking two conflicting thoughts:

1. This really isn’t that abnormal for New Wave science fiction or post-Tolkien fantasy fiction, its concerns of sex, godliness, immortality, colonialism and the dangers of both capitalism and collectivism, post-humanism, and embrace of pseudosciences and philosophy. A man believed to be born of relatively low status is actually the chosen one who will destroy the evil empire – he makes allies within the enemy, becomes a powerful superman, and ultimately conquers.

2. This is pretty wild in terms of presentation, formally adventurous, but also just thrilling and unique in its tone and performance – nothing is quite like Zardoz. Everything along this hero’s journey takes place in ways that are extremely unexpected, and the film’s conclusion is a shockingly ambivalent revenge play bordello of blood.

I think that balance is struck in Boorman’s comfort with a tale “most satirical,” as Arthur puts it in the intro. Oh, yes, it all “takes itself so seriously,” except for the whole “he draws on his own mustache and beard and flies around in a stone head because he was inspired by a children’s book” thing. It’s “playing itself straight” and also has an extended soapy titties “how do boners work” gag.

All these things work within the same general framework because Boorman knows that life is silly, technology is silly, and therefore embraces just how absurd things would get with the boredom of eternal life. Friend being our first anchor into Eternal society is key for that reason – he gives us the frame with which to watch the rest of the movie, one Zed himself has been hunting for because Eternal society is the only thing he could not possibly learn about in all his reading.

The more I pull at any given question in the film, there’s character logic and thematic reasoning to back it up. The fixation on boners is a great gag because Eternal society went to space and abandoned sleep to try to answer The Big Questions about God, love, emotion, and happiness, and now they’re so cowed they spend their days meaninglessly meditating at second level and trying to figure out boners for the tenth time. The stuff about the dangers of collectivism also stems from the origin of the Vortex – founded by capitalists who taught their children to harden their hearts to suffering, usurped by those heartless children who watched the founders realize the error of their ways, then turned back outward into the world to create an oligarchy. This place bred and led itself into oblivion.

The pacing of the film rewards multiple viewings. There’s an extended almost-wordless sequence of Zed first exploring the Vortex’s mills – this is enjoyable because Connery is very funny being scared by jack-in-the-boxes and projected videos, but it’s even more fun when you know what The Vortex is and how it’s giving away the sham much earlier than the rest of the film. Friend takes a while to figure out, but on rewatches, he instantly pops, his arc already in motion at the start of the film. Watching Consuela’s arc over the film, from total monotone (“you’re hurting me.”) to more and more emotional outbursts, it’s a great performance. Connery and Rampling both really are great in this – they’re asked to do some impossible scenes and they sell them.

And, yeah, it’s a fuckin riot of silly stuff, too. Any of the mirror falling, jumping around, fantastical editing, psychic violence and the video trial of Satan, the entire reveal of the book sequence – this stuff is, I assume, meant to be laughed at. There’s a lot of funny stuff in this movie! I think most people, even if they’re not capable of getting on its wavelength thematically, can enjoy its pretty solid pacing for memorable scenes, its wonderful aesthetics, its sheer volume of small breasts, and its laugh out loud absurdity. I tend to sell it on that absurdity, knowing many will not come along to celebrate what is, in my book, one of the great works of cinematic science fiction.

But those who do – welcome to paradise.