A surprise retrospective, a lakeside screening of my favorite live-action film (behind only Masaaki Yuasa’s 2004 debut Mind Game), turned my Barbenheimer double feature into a triple. I do not know if the programmers intentionally sought out synthesis between Oppenheimer and Barbie when programming Obayashi’s 1977 cult horror classic House, but it remained an unmissable meeting point between the impossible girlhood of Barbie and the bloody indifference of Oppenheimer.

We began our journey at 10:30am with Oppenheimer in IMAX. This was earlier than I hoped – the AMC management clearly did not receive my psychic relays for an ideal post-lunch 1pm screening, and suffice it to say it left my vibes through lunch afterward in shambles and disarray. Nolan has made his match to Interstellar, two films about the end of the world with vastly different conclusions. Interstellar argues that human ingenuity will face the end of the world and through sheer force of will, warmth, and white-hot blinding love, it will conquer impossible odds and survive. Oppenheimer, instead, argues that human ingenuity and its failure to commit to any ideals will wreak the end of the world – if it has not done so already.

Without the magic tricks of wormholes, dream layers and larger than life comic book villains, Nolan pushes himself into a corner and turns out the best filmmaking of his career. Granted, he’s hired the best of the best in terms of collaborators. Hoyte van Hoytema and Ruth de Jong reunited for some of the desert photography we saw in last year’s best-looking film, NOPE, as Oppie and various companions ride horses through the New Mexico badlands and the Los Alamos Manhattan Project site. Ruth de Jong crafts wonderful, meticulous, memorable spaces alongside newcomer Emin Hüseynov, some based on historical record, others intentionally never recorded. Composer Ludwig Göransson was Tenet’s most valuable player, and he turns in breathtaking work here as well, ratcheting incredible tension and release as we build toward the Trinity detonation. Among the greatest editors alive, Jennifer Lame keeps these sequences legible and also disorienting.

It is insane a film this dour and this nihilistic is being sold as part of the greatest double feature in the history of summer blockbusters. Part of that is that when the pyrotechnics do go off, they maintain a wonderful balance of genuine spectacle and distinct horror. The Trinity test shredded my ego. It made me feel small within my seat. The aching pain of the remainder of the film, carried in Murphy’s once in a lifetime performance, withered me to a trembling husk. Most of my companions did not have such a hard reaction to the film. We made jokes about Joshes Peck and Hartnett, Branagh’s flexible accent work, and lamenting that the Pugh character is saddled with the film’s two worst scenes, the sex scenes no one quite knows what to make of beyond recognizing that it paints Oppenheimer and Tatlock as pseudointellectual assholes. We mostly loved the film.

I really do think Murphy is walking an incredible tightrope in this film. To play a man so uncommitted to anything beyond forward momentum shatter upon completing his greatest achievement is difficult enough to make compelling, but on top of that, you have the fragmented timeline presenting ego death Oppie well before we’ve seen him at his most confident. He (and Nolan, and Lame) have managed to make a character arc that works both when considered chronologically and in the sequence the film presents, and they’ve done so without aggrandizing a character who is rightfully called a crybaby and criticized for his inability to commit to any values or moral scruples until he’s already done his worst. “You can’t commit the sin and make us all feel sorry for you,” Blunt’s Kitty Oppenheimer gets to state near the middle of the film – I don’t find myself ever feeling sorry for him, but once he can see what he’s done, it’s a scathing indictment of the world we’ve built since.

It’s not all the abyss. Nolan gets some hokey jokes in, fills the screen with fun characters, and builds a community that feel like they have genuine relationships, politics, ideas and ideologies. I agree with the sense that there was another hour of the film on the cutting room floor, only sacrificed to get that 70mm print out there, because there’s propulsion around these wonderful characters on the side who never quite get their chance to shine (specifically, Olivia Thirlby and Josh Zuckerman jump out as actors who might have had a bunch of material cut). Matt Damon, Robert Downer Jr, David Krumholtz and Josh Hartnett all get to bring some life back to the film – it’s a pleasure to see Alden Ehrenreich get to play off of a revitalized RDJ. The moment to moment thrills of reunions, breakthroughs, and “men sitting around a table making big decisions” are the stuff I knew Nolan had in him. It’s the ecstatic he reaches into here, and the nuance with which he engages in this film’s politics, that had me very much surprised.

We continued on to lunch, which took too long to come out, played with pets (including one very heavy cat,) and made our way to Barbie at 5pm. I connected Gerwig to Ang Lee in my review of Little Women, a film which shared a striking humanism and sensitivity for modest joy with the master Lee’s Sense & Sensibility. The most obvious analog to Barbie, then, would be Lee’s Hulk, a formally ambitious, visually impressive adaptation of a seemingly simplistic property that’s being interrogated with more thoughtfulness and purpose than previously. But Lee’s film’s interrogation is achieved by amping the melodrama of the film to a mixture of psychological character study and Greek archetypal mythic storytelling. It digs very deeply into the core relationships with a lot of grimacing and distress, and it offsets that discomfort with its incredibly striking visual sense.

Gerwig goes a different direction here, though I would argue it still matches that humanistic approach. For one, obviously, Gerwig’s film is a sex comedy about the absurdity of gender norms and a political farce about systems of power and oppression. While I think it still very much takes seriously the emotional states of Barbie, Ken, and the two “real world” leads Gloria (America Ferrera, who is really great!) and her daughter Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt) it’s not nearly as built upon the Trauma of The Absent Father or The Oedipal Crisis. It trades Freud and Sophocles for intersectional feminism and fragile masculinity, and I’d argue a more pop-focused Twitter rendition of those subjects than Lerner or hooks. (Which isn’t to say Gerwig isn’t reading those books, too – just that what ends up on the screen is broader, more digestible, and familiar to those of us terminally online.)

But for another major difference between Barbie and Hulk, Gerwig steers clear of declaring a true villain. There are antagonists – Ferrell’s condescending “ally” profiteer, Gosling’s turn as the meatheaded version of Ken – but they never become anywhere near as unsympathetic as Nolte’s Brian Banner, a disgusting snake of a man. And that is, of course, very intentional – Gerwig has spoken about how this film’s feminism is a “rising tides” feminism examining how failure to understand how gender roles work and the standards they enforce sink everyone into the ocean. Gosling really is born to play Beach Ken, a sympathetic but deeply flawed man whose impotence and ignorance are so readily willing to channel into vengeful malice. It’s an arc we’ve been told plays out regularly these days, the alt-right pipeline that we’re told starts from men not being validated for the sexual desire.

It’s in this morass that Barbie sets itself, and it elegantly dances around getting mired in any real-world ugliness for all too long. The longest extended sequence of exploring these themes, Ferrera’s monologue, is somewhere between a “clap-rather-than-laugh” gag suited to the modern comedy scene of Hannah Gadsby and Bo Burnham and a tour de force acting moment for Ferrera. It worked for me, and it’ll work even better for the huge audience of people seeing this that aren’t embedded in daily queer lefty feminist close readings of mass media. By otherwise keeping things relatively compartmentalized, it’s able to keep its levity at the forefront, a lovely confection.

While picking standout cast members aside from the leads is difficult – I really enjoyed Alexandra Shipp as Book Barbie, Rhea Perlman as Ruth, and Kingsley Ben-Adir as Benvolio Ken – it’s not hard to shower production designer Sarah Greenwood in praise. The Barbieland world looks genuinely incredible – it’s such a wonderful work of production design, and the amount of delight clearly put into making every visual choice work is really astonishing. It’s a degree of visual imagination I certainly wasn’t anticipating out of a Gerwig movie based on her prior work (though Little Women is a great looking film) and it was thrilling to see it come together so wonderfully. There’s also a couple sequences toward the end of the film that invoke the work of Donen and The Archers that I think are special both as staged and as conceived, and it’s really wonderful that they were able to get those scenes in front of so many people.

If I really was going to make the comparison to another film’s success, Barbie isn’t Hulk, nor is it Josie and the Pussycats or Clueless as I’ve seen some people say. Barbie is Austin Powers course-corrected to ensure audiences actually get the joke this time. Austin Powers is an archetype of the sex machine hero of the patriarchy turned into a freaky little goblin, and by 2005 half the male audience just wanted to be Austin and actually would ask women out loud if they “make them horny, baby.” I think Gerwig tunes this film so that everyone understands that while we love to see the Kenergy, we do not want to be Ken. Ken doesn’t want to be Ken. Ken’s going to be Kenough instead.

At this point, I was pretty tired. We’d partied a little too hard the night before Boppenheimer anyway, and eating only one meal and some cheese curds was not a recipe for success. But Obayashi’s House is a longstanding personal favorite, and like when I saw Zardoz a few weeks ago (I went long on that one too,) it felt like a personal welcome back to Madison gift for me to see it on a big screen surrounded by friends who’d never seen it before. It was relatively low stress to be reunited with it again, and it really did feel like the appropriate meeting point of the two films I’d seen already.

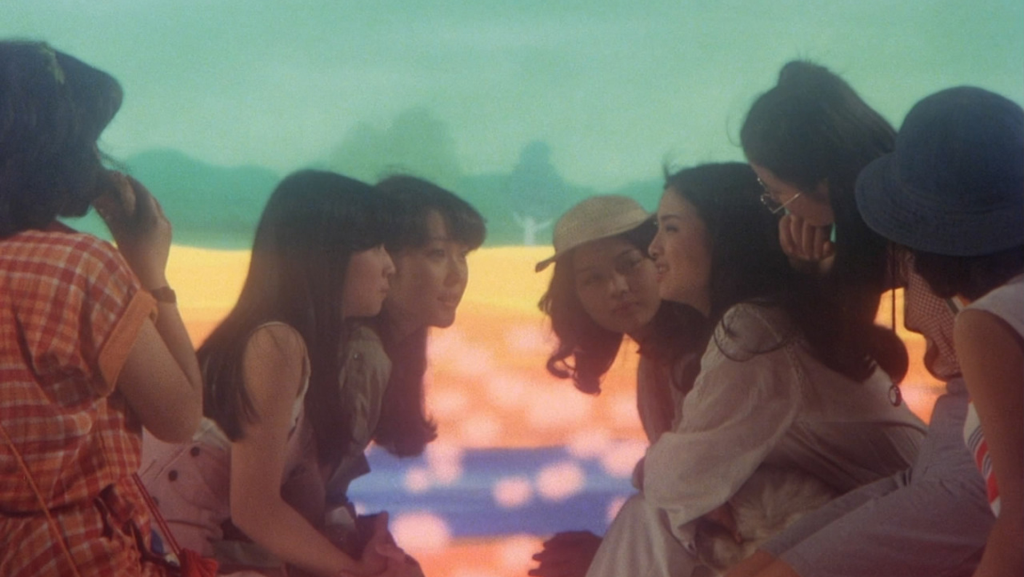

Obayashi’s history in advertising brings forward the comparisons to Barbie in a visual flair. We see absurdist comedy with stop-motion mechanics, animated backgrounds to live action sequences, flashes of sparkles and color that almost always get a laugh from the audience. But our characters, too, are stereotypes of girlhood popular in the booming shojo market of the period. There’s three named for their personalities, Gorgeous, Fantasy and Sweet, and four named for their hobbies, Melody, Prof, Kung Fu and Mac. Based on how fun Kung Fu is in this film, it’s too bad we never see Karate Barbie in the Gerwig film.

These seven friends are planning their summer vacation, when Gorgeous is thrown for a loop. Her father is remarrying eight years after her mother’s death – unfortunately, he’s kept this a secret until the last minute, and introducing his new wife throws Gorgeous into a tailspin. She decides to cancel her family vacation and invite her friends (whose plans were thrown off by an unexpected pregnancy) to her Auntie’s house. This all plays out like a slice of life comedy, not unlike some of the TV dramas still being made today. There are cut-ins, zooms, even title cards clarifying all the names about twenty minutes in. It’s really, really charming stuff, and it lends a layer of safety and camp to the proceedings long before the horror begins.

But the tropes of these friends also end up playing them against one another, never in ways where they are openly fighting, but in ways where they occasionally diminish or dismiss one another’s concerns, limiting their expression. There’s a great scene where the other characters are trying to think logically and exactly mimic Prof’s gait and gesticulations – it’s cute, but also shows how much confidence they lack in themselves. Prof also gets hit with a “you’re so pretty without your glasses” remark that doesn’t register with her as meanspirited, but it is striking. Mac is probably the hardest to swallow – her thing is eating too much, and the other girls make comments about her weight (which she objects to frequently!) Fantasy really gets the worst of it, constantly having her witnessing the supernatural horror which will swallow them up as her daydreaming and imagining things. If these roles weren’t so defined, they wouldn’t be so easy to entrap – and Auntie’s magic snares don’t have to work very hard to pull them to their dooms.

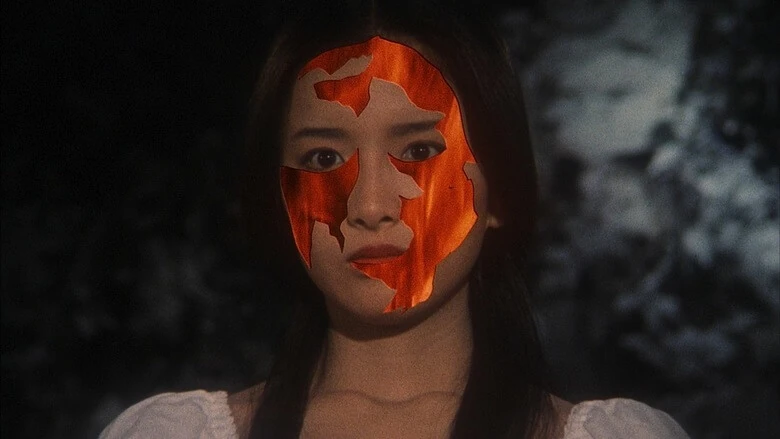

House’s connection to Oppenheimer may be a little more subtle, but it’s a matter of understanding the horror of the film. In an early sequence, Gorgeous shares the backstory of her Auntie in the form of a silent film all the girls watch together. She’s a young woman who became affianced to a young doctor in a small town. The young doctor is drafted into World War II – he promises to return to her, and she promises to wait for him. When he’s shot down, she decides to wait for him for the rest of her life in the titular house, and after her sister is married, she waits alone. And she’s really, truly alone – the last time Gorgeous has seen Auntie was ten years ago, when Gorgeous’s mother was still alive. When Auntie receives the note of her lover being missing in action, we see blood fall from her hands and a baby cry – we hear this baby’s cry again late in the film, during the climax, when a deep blow has been done to the ghost running the house.

This backstory frames the film’s central haunting as a tragedy. After the war, this widows who survived her dead was paid no real mind – if her pain prevented her from simply finding another willing man, she was isolated and abandoned. In a moment where Fantasy frames this devotion as romantic, the film cuts to the atomic bomb. Obayashi himself was a child of Hiroshima, losing all his friends in the bomb at age 7. A diary found toward the end of the film reads, “There are no young women in the village now. I’m all alone.” This is ambiguous, as it may have been written before Auntie died and became the witch-spirit haunting the old house, or it may be after she’s eaten all the young women who were left. This violence against Auntie, the lack of care paid to unmake this single-minded devotion, creates a cycle of violence and misogyny which leads to her quite explicitly becoming a predator upon the virginal women who she entraps in the house. It is a chain reaction, the violence begetting violence beginning with the war and ending upon seemingly kind, innocent young women who know nothing more than the basics of history book lessons in school.

It is this sadness which underlies House’s scares, and yet Obayashi maintains incredible levity throughout the film. The visual invention on display and his incredible management of tone (including the expert use of whiplash) is the anchor through what is, admittedly, a story told in bizarre sequence and, underneath the effects, a pretty sad conceit. The aforementioned sequence in which Gorgeous tells her Auntie’s story is preceded by a child reading a picture book about the trains of Tokyo – it zooms in, and briefly, the film becomes animated in the style of the picture book, zooming along past Mount Fuji. When the background changes to a grassy glade, Sweet leans in to ask Gorgeous about her Auntie – they talk about this in front of the animated background, beginning the story, before cutting to Auntie’s story. There’s dancing skeletons, carnivorous pianos, bucket-butt slapstick, butt-biting and cats, cats, cats.

The fact remains no one else could possibly have made House. In order to replicate the feeling of it, they had to release two epics on a single day. Anyway, do Oppenheimer before Barbie. You’ll need the Kenergy before going to bed.