I’ve written previously in brief about Desert Golfing, a recent intriguing mobile game. It’s a simple game where the player swings a ball across a desert into holes, a ticker keeping score all the while. The game’s escalating difficulty is accompanied by surprises in the desert and the player’s continuing mastery of the physics and control of the ball. It’s by no means the “best iPhone game of 2014” (it’s likely that’s Threes!, which spawned a legion of imitators) but a recent patch solidified its place as one of the most interesting, given credit by its inclusion as a Nuovo Award finalist for the annual 2015 Independent Games Festival.

Desert Golfing now has two canonical “endings,” each a variation on the same. Notably, it’s not likely the creator, Justin Smith, would reach either. He considered a hole roughly 500 before the first ending to be “impossible,” meaning he was nowhere near encountering the first when it was uncovered, and the second only requires more skill. Albeit both the game’s endings specifically place emphasis on that which came before the ending, I will fulfill the cyclical problem Desert Golfing addresses by reading its endings and the implications they raise. This piece, for what it’s worth, will presume some familiarity with Desert Golfing, meaning those who haven’t played the game should read my previous piece.

ENDING ONE: AN ENDLESS HORIZON

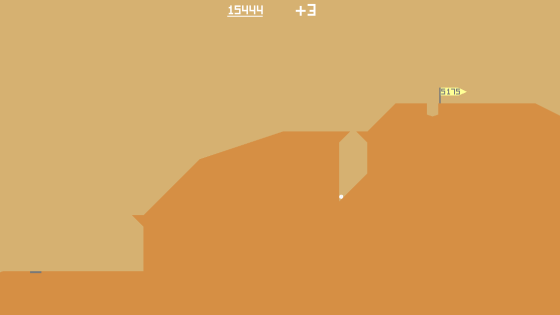

The first was beautiful in its simplicity; around hole 3300, there is nothing left to see in the desert. It very nearly flattens, the desert itself expanding ever-onward into the tens of thousands. A handful of players soldiered onward, enjoying the simple golf swing mechanic enough to pass through the plateau, discovering nothing.

This ending was poetic. Its ending is not a closed circuit; rather than create endlessly propagating content generators, Smith allowed the game to close itself without “cutting to credits.” The purpose throughout the game had been to play onward without promise of reward; to not grant that reward is significant. But to end the adventure without closing the play experience entirely allows the first 3300 holes to be “the challenge,” and its closure releases the player from that stress and struggle. To end the desert’s dunes and mountains gave the game a serenity and sense of closure.

Narrative games have experimented with similar endings. Dragon’s Dogma, a combat-oriented action roleplaying game by Capcom’s adventure game staff (alumni mentioned on Wikipedia worked on the Devil May Cry series, the Resident Evil games, and Breath of Fire) concluded by questioning the concept of an adventure’s reward; the player character becomes a guardian deity of their world who can no longer interact with the world itself. Left to simply walk about and not interact, the player’s only real gameplay interaction is to kill their character. The narrative result or motivation for this suicide appears vague when studying discussions of the game’s ending, but the player’s motivation for ending the game is likely boredom, and it is possible the guardian’s death actually puts the world in danger again. This ending, put into context by a game light on story and heavy on playful combat, indicates that the reward was not the protection of the world or the ascent to godhood, but the play which came beforehand.

Both games share a vast emptiness after the primary adventure. The player has transcended the challenge, and they are left in a void. This is, to some degree, true of any game with a conclusion. Excepting professional play, there are no out-of-game rewards for completing a game, and content unlocked post-game is usually just considered the “true ending” of the game to those who seek more than the game’s primary conclusion. This void is generally white scrolling credits on black screens, followed by a trip back to the title screen. Open world games like the Grand Theft Auto games or inFamous often just drop you back into the world, sometimes with a tooltip saying something like, “Congratulations on finishing [game]! We’ve made much more to see, so get back out there and enjoy yourself!”

Other narrative games that don’t end so literally with extended inaction still place their characters within a void. The fate of Booker DeWitt at the end of BioShock Infinite is hardly as simple as either a victory or a tragic failure, and its results place into question the “purpose” of that which came before. Metal Gear Solid 2 drops Raiden into a confused world where little seems true, an ending as convoluted with conspiracy and doubt as The Crying of Lot 49 or, to a lesser extent, Inception.

These stories, along with the aforementioned games, end intensely, simultaneously placing extreme emphasis on their endings and calling into question the role of an ending in determining thematic purpose. Too often the critical reading of a text, whether it be a book, TV series, game, or piece of visual art, will place too much focus upon the conclusion of a piece. Subplots, events in the middle of a text, and undercurrent themes are ignored in favor of the most dramatic reading of the text. Utilizing the premise, climax, and ending only, the reading determines the entire thematic wardrobe of the text. It’s these readings that allow Mass Effect 2’s countless statements about parent/child relationships to go unmentioned, or the graphic “Chico’s Tape 4” to go uninspected in reviews of Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes.

A SIDE STORY

Side stories perhaps seem less relevant in film. Maybe the film requires a certain number of characters to function, and so side characters are sometimes given subplots and charismatic actors that are more present for entertainment, mood shifts, or pacing than for thematic relevance. Often, films spare on these subplots receive more acclaim for being focused or intense, whereas films with numerous plotlines often are saddled with frivolous “comedy” labels because of the tone of these plots. Wes Anderson films are countlessly placed in this context, even with harsh content and thematic depth, such as those in The Royal Tenenbaums or The Grand Budapest Hotel, rather than as serious works, as are ensemble films like Love, Actually or Pacific Rim. As a literature student, I’ve been instructed to deeply study subplots and alternate themes when writing essays, but literature courses focused upon a genre or period of texts only give time to the dramatic reading of the text and one or two popular subplots, regardless of a given text’s length or depth. But a literary author gives page time to these plotlines because they are significant in the author’s purpose; at least, this is the accepted reading by students of literature.

Games are curious in this manner. Because of the nature of development studios and the modern multi-studio triple-A game, entire portions of a game might be developed by different studio teams, or another studio entirely. An infamous example would be the boss fights in Deus Ex: Human Revolution, chapter climaxes notoriously out of touch with the rest of the game’s purpose and outsourced to another development company. A game like Mass Effect, Dragon Age, or Assassin’s Creed is forced to use this kind of parceled-out development, sending the creative team onto the next game entirely while the designers, programmers, and artists put the final product into motion.

What that means is: for a team of maybe ten or so people, the perks system in a game like Call of Duty may be the entire game. One team probably slaved over the base-defense game in Assassin’s Creed Revelations before sending a couple of their programmers to fix bugs and a couple animators to help finish up protagonist Ezio’s swimming. It’s likely that different people design the loyalty missions in BioWare games. And those three sidequests about the fact that sheriff Emily Watson can’t cook in Deadly Premonition may have been SWERY’s concept, or it might have been one of its team member’s pet projects. The stories of game development are rarely so concrete that we can effectively ascribe these things to specific people. It’s one of the reasons dev diaries like those available with the Double Fine Adventure Kickstarter or Cara Ellison’s “Embed With Games” series are so valuable, and why books like Masters of Doom provide deep insight.

Dragon Age II’s default hero, Hawke, and his companions, each given lengthy stories of their own.

The existence of these teams calls into question the “dramatic reading” of most games. Artistic intent is hard enough to verify, and where film is often guided very seriously by its director and subordinates, the complexity of game design forces the director to put things out of their own hands somewhat; while, surely, the director and producers have final approval, entire scenes of a game might be crafted without their input, only modified as a finished product. This means that large games like these are likely to have parts of the game conflict with each other, the way a TV show might have a continuity error between episodes because a different writer or director took over that didn’t watch/read the previous episode carefully enough.

However, games like Gunpoint, Dust: An Elysian Tail, and, yes, Desert Golfing, are developed by one author; the first and last were also published without editorial approval, barring a pass by the distributor that the game didn’t simply crash on startup. It’s much easier to ascribe an authorial purpose to elements of these games. Even games by small teams, like Bastion and Transistor by Supergiant Games or Gone Home by The Fullbright Company, are likely to have a cohesive sense of purpose. Both Desert Golfing and Bastion have dramatic endings which place emphasis on consideration of the game prior.

Desert Golfing hones the “prior game” to almost entirely the play of the game. Mild aesthetic changes and a few props have appeared to this point, but nothing severely alters the player’s understanding of the game between the point at which they observed the color change (often around hole 2100, when the game has fully shifted from orange-yellow to a pink) and the game’s original conclusion around hole 3300. It’s an ending which requires reflection and may inspire nostalgia for a game now effectively completed.

ENDING TWO: COUNTLESS MOUNTAINS

On November 21st, a patch for Desert Golfing went live which simply read “revamped the later holes. rock is saved. more kid friendly touch screen.”

Wait wait wait wait. pic.twitter.com/7pJ3E1zUAV

— Brendan Keogh (@BRKeogh) November 23, 2014

The primary nature of the new content is an endlessly propagating series of mountains and gaps, extending as far as 12000 holes without anyone finding a new plateau. Brendan Keogh, one of Desert Golfing’s major champions, found himself at a loss when he uncovered that a frustrating hole reappeared in duplicate only 105 holes later. The reuse of content isn’t as severe as that might make it seem; I’ve hardly noticed if any holes have repeated themselves moving from roughly hole 3400 to hole 6000, though the hole he posted is one of the more frustrating.

Replacing the serenity of Desert Golfing’s plateau with mostly-difficult levels and persistent color-cycling (which begins around hole 1000, but, before the patch, ended around hole 3000) refocuses the reading of the game on its primary content. The original ending allowed closure and peace, a statement almost as loud as the game’s simple, satisfying gameplay and escalating difficulty. Players are thrilled that the game is extended, saying that “the game is fun again;” they’re thrilled to spend eternity in Desert Golfing. Others are unsatisfied; Keogh followed up his discovery by considering surrender.

But this change forces continued consideration of the game’s mechanics upon its player, rather than its body and length. If we have no ending to consider the “dramatic reading” of Desert Golfing’s conclusion, then we’re forced to continue tuning our understanding of the arc of the ball, the strength of a given swing, and the way the sand catches the ball at different inclinations. Alternatively, we surrender, falling upon the unforgiving spikes of turf that obstruct progress.

Perhaps the most striking thing about the change is its total erasure of the game’s prior ending. It’s at least as dramatic a change as Blade Runner’s between its theatrical cut and director’s cut, yet there aren’t likely archived versions of Desert Golfing available to the public. Maybe a savvy collector/historian might have decided to hold off on patching the game on an iPod Touch to preserve its old ending, and Smith likely has archived versions of the game’s original ending. But to those of you reading this post, a playable version of the game’s original ending is gone; it exists only in memory and in recorded media, like this video scrolling through the game’s original 10000 holes (around minute 19 is where the game’s original ending begins.)

This mutability further emphasizes the game’s statement about the emphasis we should place on the actual text of a text rather than its highlights and conclusion. In a few months, maybe Smith will change the ending again, and the ball will be carried away by a UFO on hole 10000. But, until then, we’ve been left to hold infinity in the pockets of our pants, and eternity in Desert Golfing.

UPDATE: Twitter user @loaphn has informed me that the new ending of Desert Golfing actually features a carousel of levels; each player starts at a different point, which explains why I don’t recall encountering any duplicates. While the implications of dissociating the player base at the game’s conclusion and isolating the players to more individualized deserts expand on what I’ve written, the original text stands, so I’ll let it rest. @loaphn also informs me that they have every version of the game archived: thanks!

Pingback: This Is The First 10,000 Holes In Desert Golfing | Kotaku Australia

Pingback: Holding Infinity In The Pocket of Your Shorts | All My Friends

Pingback: Games of 2020 – What’s Old Is New Again | All My Friends